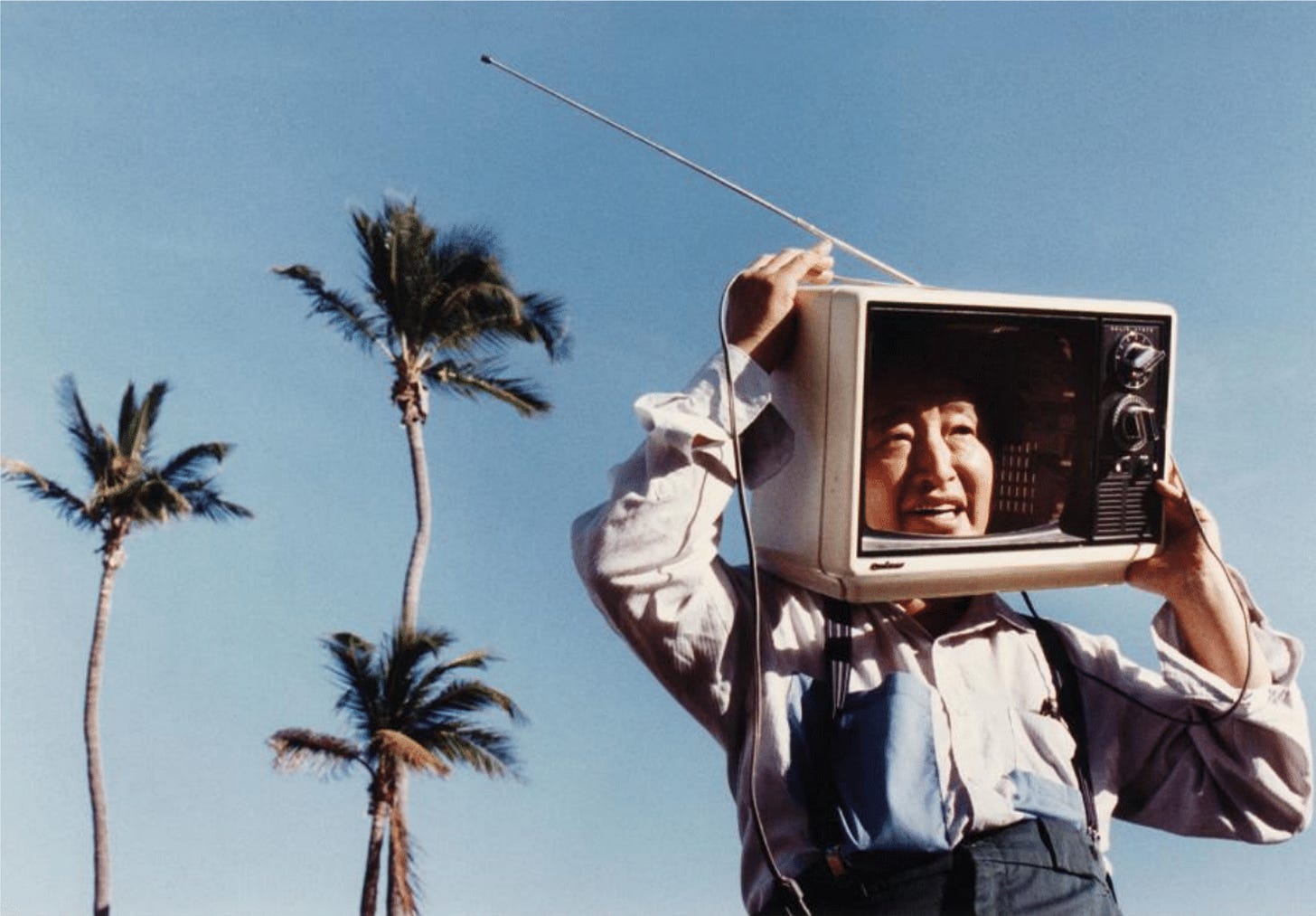

Moon Is the Oldest TV

Nam June Paik composing the future

Some of us seem to come out of nowhere to become who we are, paving our way as we go along, undeterred by the uncertainty of where it may lead or the hardships we may encounter along the way. Korean American artist Nam June Paik (1932-2006) is definitely one of these people. Trained as a composer and classical pianist, his trajectory to becoming a pioneer of video art did, however, have an “aha!”moment. He credits John Cage’s (1912-1992 ) 1958 concert he attended in Germany, to have enabled him through improvisational performances and found sounds. It was under Cage’s influence that he embraced these new explorations of chance in his art making, and especially with sounds, where he gave up control and allowed the art just to happen. Experiencing Cage’s freedom from conventions was decisive to Paik.

Friendships were central to Paik’s practice throughout his life. He participated in George Maciunas (1931-1978) Fluxus movement, this small but international interdisciplinary network of artists interested in experimental art performances that emphasized the artistic process over the finished product. They sought to destabilize relationships between performer and audience and questioned the conventional boundaries of art and its definition. Yoko Ono (b. 1933) and Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) were also part of Fluxus and became lifelong friends.

In the U.S. where he moved in 1964, he extended his network of artist friends to include the classically trained and advocate for avant-garde music Charlotte Moorman (1933-1991). Their partnership was long-lasting and generated extraordinary performances including Variations on a Theme by Saint-Saëns (1964) where, wearing a transparent cellophane gown, Moorman begins to play the first few bars of The Swan; abruptly, she puts down her cello and walks across the stage to a large oil drum filled with water. She climbs a stepladder to the rim of the drum where she perches briefly before lowering herself into the water until she gets completely submerged. With the dress and hair dripping wet, she returns to her seat to finish The Swan. and Opera Sextronique (1967) which was interrupted by the arrest of Moorman, who was performing topless.

Paik and Moorman fused music and sculpture, performance and video. She credits Paik to have advanced the cello after centuries of stagnation and explains that his breaking of instruments was not about destroying but releasing them.

Around this same time Paik began to experiment with TVs and other audio-visual equipment. Intrigued by how they could be instruments of education but also of manipulation he experimented with distorting the images to reveal their manipulative power he wanted to remind us that these images were representations of reality vetted by the powers that be and not reality itself. He seemed to “recognize the corrosive possibilities that technology might play on our sense of self, community and faith.” Nonetheless he aimed to “inspire a resistance to mass media as unidirectional; he wanted us, as audience members, and as citizens of the electronic age, to take back some measure of control.”1 Hence his sculptures and the technology involved in creating them being transparent, all cables and connections visible. He wanted to humanize technology and explore its possibility to connect people.

Paik was not alone in turning his gaze toward the new medium. In 1959 the Italian neorealist film director Roberto Rossellini (1906-1977) produced his first tv show L’India vista da Rossellini, an account of his recent travels in India. By 1964, the director had made television his permanent home. In a more utopian view, he believed that “modern society and modern art have been destructive of man; but television is an aid to his rediscovery”. He was convinced TV was a tool to elevate human consciousness and saw the medium as an instrument to democratize education. Rossellini saw in the new technology an intimate connection with transformation and hope for the future.

For Paik the transformation the future would bring was the information highway, a term coined by him to describe how new technology would soon allow for transcontinental communication. A visionary artist, Paik’s work was very much attuned to the rhythms of the changing world.

Now, artists may not have clairvoyant powers but some do develop skills to imagine the future beyond what many of us think possible, as Paik did. And why is it important to imagine the future? If we can develop the skills to imagine a different future from what we have, we may get away from the limiting state of mind which tells us that nothing will ever change. Imagining different futures may lead to tangible action and avoid history repeating itself.

The Bass Museum’s exhibition Nam June Paik: The Miami Years uncovers the little-known history of the artist’s life in Miami Beach, where he spend his last 10 years while continuing to explore communication and technology. The opening included a conversation between the art historian, curator of film and media arts and authority on Paik, John Hanhardt, and the exhibition curator Dr. James Voorhies as well as the screening of the excellent documentary by Amanda Kim released this year Nam June Paik: Moon is the Oldest TV.

Nam June Paik: The Miami Years is on view at The Bass Museum till Aug. 16 2024.

Hsu, H. (2023, March 29). How nam june paik’s past shaped his visions of the future. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/how-nam-june-paiks-past-shaped-his-visions-of-the-future