Threading Ideas

Tracing marks and stitching stories: up close at this year’s Miami Art Week.

In preparing for a fun, busy week, I usually brace myself for a certain level of noise: the loudness of crowded, enclosed spaces; the congestion of both pedestrian and car traffic; the visual overload that starts to feel like noise by the end of a long day. This year’s Miami Art Week was no different. However, what caught my attention was unexpected: when looking for trends I noticed the prevalence of drawings—figurative works and abstract markings—displayed in many galleries. And they felt quiet, as did Daniel Buren’s regatta, where striped sailboats glided across Biscayne Bay.

The focus on lines and shapes in the drawings drew us in, inviting close and intimate engagement. Historically, drawings have been exhibited as works that foster a unique connection between the viewer and the artist's process. Their raw, unfinished quality—a glimpse into the act of creation—often highlights the intimacy of the gestures, encouraging us to perceive them as moments of becoming rather than completed statements. Delicate and intriguing, these gestures provoke curiosity and reflection.

In my research into the medium, I came across MoMA's 2010 exhibition On Line: Drawing Through the Twentieth Century, organized by Connie Butler(1). This show explored the transformation of drawing in the 20th century, as artists critically redefined traditional concepts of the medium. They moved beyond paper extending the line into real space, challenging the relationship between art and the world including performances and films.

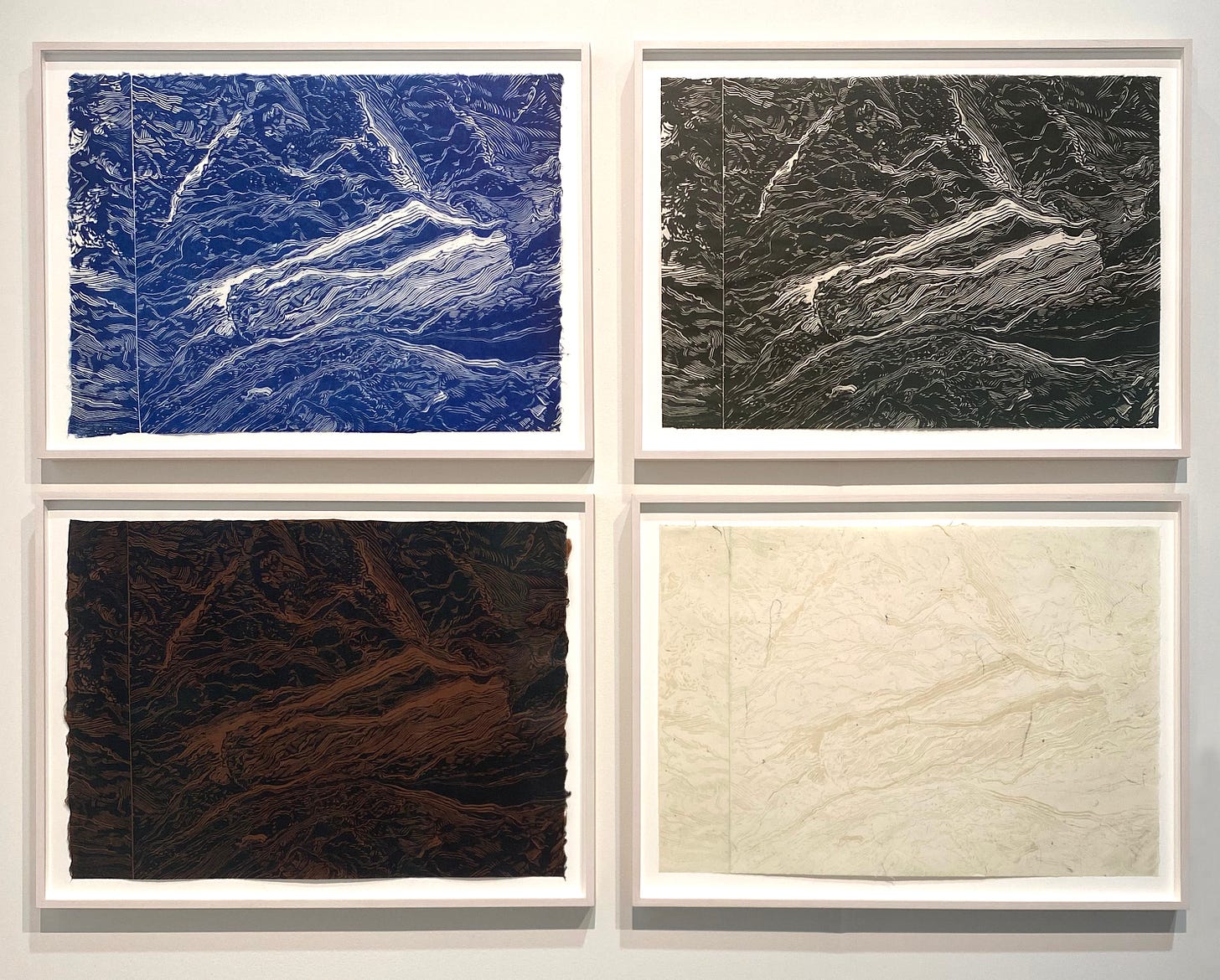

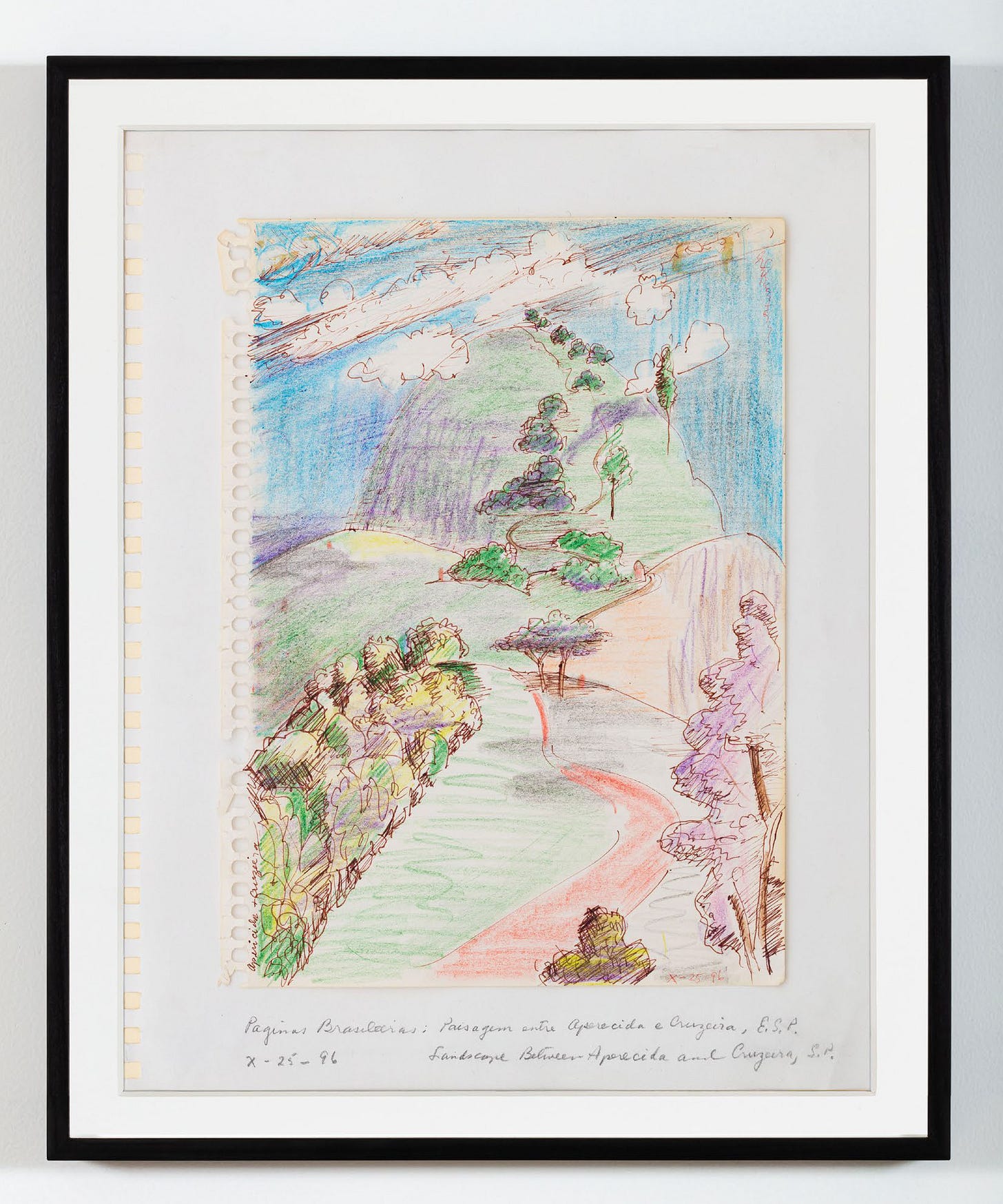

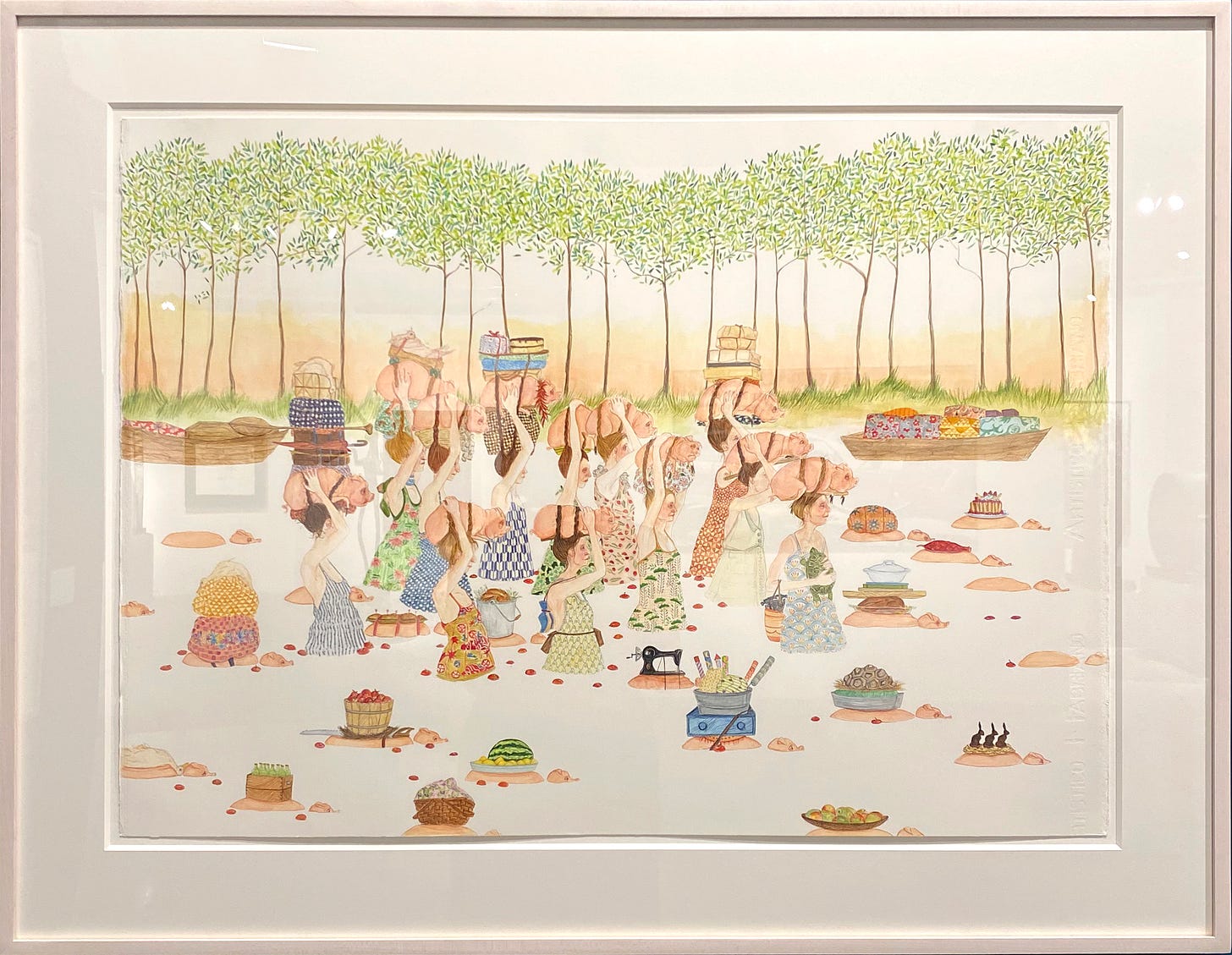

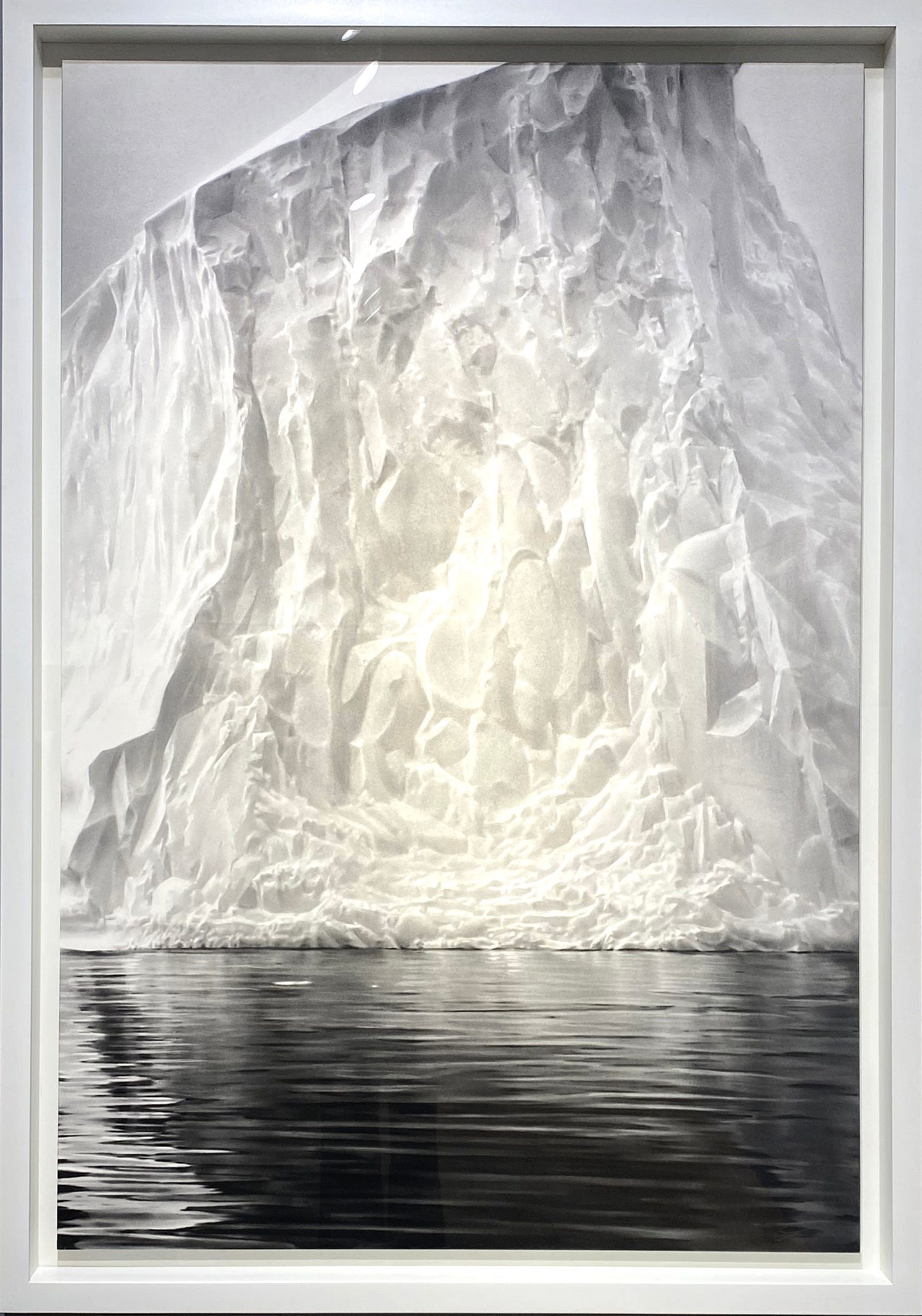

Fiber art and various forms of markings stood out this year. With roots in the 1960s and 1970s, textiles have long challenged the boundaries between craft and fine art and are now regarded as more than just a trend(2). This era also marked a significant shift, legitimizing the association of an artist's practice with their personal life and memories. Feminist movements further expanded these boundaries by reinterpreting domestic crafts as art. Today, fiber art remains a powerful medium for personal and political expression for all genders. Some of what we saw includes: Lee Shinja’s 1980’s tapestries that attempt to catch changing light; Jordan Nassar’s embroidered fictional landscapes; Adolfo Riestra’s drawings addressing human connectedness; Robert Longo’s charcoal depiction of an iceberg; Amy Cutler mysterious, surreal worlds; Madalena Reinbolt’s highly pictorial and dramatic wool paintings, as she called them, sometimes done in the evening, after retiring from her domestic work.

Here is some of what we saw at Design Miami and NADA:

For the latest iteration of the Miami Beach’s public art initiative Elevate Española, Miami-born and Los Angeles-based artist Jen Stark debuted Sundial Spectrum, her first public installation in her hometown. More on that can be found at the article written by yours truly for The Art Newspaper.

At the main show Art Basel Conversations offered an engaging series of discussions featuring artists Shirin Neshat, Harmony Korine, Paul McCarthy, and Jill Mulleady, curator Hans Ulrich Obrist among others. A standout session for us was What can public art do? a conversation between Kate Gilbert, Executive Director of the Boston Public Art Triennial and Dr. Deborah Willis, artist, curator, and historian, moderated by Kimberly Bradley, Conversations Curator at Art Basel. Seeding the environment, staying local, and remaining true to specific contexts, they discussed how public art also serves as a platform for activism with the capability of retelling stories, fostering deeper engagement with the community. All sessions are available on the Art Basel’s YouTube channel. Below, some of the what we saw at the main show:

We had the opportunity to attend William Kentridge’s musical theater performance, The Great Yes, The Great No, which was the highlight of our week. Set aboard a ship sailing from Marseille to Martinique in 1941, the production fictionalizes the historic wartime escape from Vichy, France by prominent artists and thinkers of that time, including André Breton, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Wifredo Lam, Anna Seghers, and Victor Serge. Space and time are fluidly rearranged and additional characters, like Frantz Fanon and Suzanne Césaire, are invited aboard this symbolic ark, transforming it into an allegory of displacement as well as a vivid portrayal of humanity’s desires and disasters. The actors use cardboard photographic masks, which they shift throughout the play, creating a fluidity of identity among the characters. Kentridge explains that the work also serves as a historical reflection on Europe’s transition from rationalism to surrealism and its evolving ways of understanding the world. He further notes that the destination is an imagined Martinique, taken from writings and perspectives of various individuals. Watch here to an interview with Kentridge.

Great art choices in your article today!