The unbound universe of Helen Frankenthaler

A visit to the most recent exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, Italy.

Art as creation is, at its core, an act of “doing”. Opposed to nature, which also produces things, the artistic creation is not the result of a “cause” or a “reaction” but an intended action fueled by a free intention to “do”, for something to exist. This intention behind any artistic creation, is what distinguishes it from any other form of existence and grants the work of art a status beyond its own materiality. Abstract art is a good example of this. It is not by its material look that an abstract work of art can be seen as such, especially since it also lacks any figurative reference, but because this very same tangible non figurative object refers itself towards something beyond its material existence, that is, to an intention of creation. This intention can only come from the freedom and consciousness of the artist, his or her desire to create, and whose creation is always a search for that absence of reference, that realm beyond sheer matter, beyond technique and beyond the literal.

Helen Frankenthaler’s intention is, as she famously said herself, to go against the rules or ignore the rules, that is what invention is about. Recognized nowadays as one of the most important post war American artists, Frankenthaler artistic career is one I would define as a becoming, an example of constant transformation and hence, a constant search for what lays beyond the predefined, the expected, the rules, the cause. For this reason, as she perfected her very personal soak-stain technique, she managed to give an instance of existence to the ungraspable character of Beauty.

The exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi, in Florence, Italy, shows very clearly how this search for beauty became clearer to Frankenthaler and little by little took shape in her increasingly shapeless canvases. I believe this monographic exhibition that shows her transformation journey has a more meaningful raison d’être in such a museum, this being one without a permanent collection and, so, always transformed according to the exhibition it holds inside its walls.

Helen Frankenthaler, Painting without rules is an exhibition that takes us spectators through the personal and artistic life of the artist, a woman very much of her time but who knew how, from her ephemeral human condition, paint the unfathomable, the eternal. Through the exhibition we discover how she began as an artist, the works of art and fellow artists that influenced her, the personal relationships that contributed to her artistic becoming and how all these elements, apparent circumstantial details, led her intuitively to become a pivotal figure in the emergence of Color Field painting.

Starting With A Flashforward

The exhibition is the most extensive retrospective ever done in Italy on Helen Frankenthaler. Curated by Douglas Dreishpoon, director of the Helen Frankenthaler Catalogue Raisonné, it presents the artist’s large scale canvases, some of her sculptures as well as works on paper, all in dialogue with other artists' works, contemporaries of Frankenthaler herself. This comparative dynamic between works allows the exhibition to explore more in depth Frankenthaler’s world as well as her evolution as an artist.

Each room walks you through the most important periods of Frankenthaler’s life and career, from her early years when she was greatly influenced by Jackson Pollock and Rothko, up until the early 2000’s paintings where her artistic language, as we know it today, had very much sinked in. Despite being curated in a chronological order, the exhibition begins with a flash forward that takes us to the middle of Frankenthaler’s career in the 70’s. Perhaps this was a curatorial decision designed to introduce the essentials of her artistic language to the general public, whether knowledgeable or not about her work.

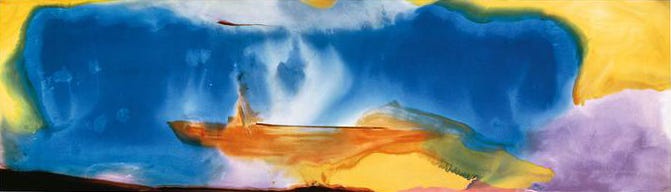

In the first room are displayed paintings, on canvas and paper, as well as a sculpture but without a doubt, the room is largely dominated by Moveable Blue (1973). The large blue and yellow canvas already announces to whomever walks in what their experience will be all through the show, namely a journey towards unbound color. My first impression as I stood in front of this abstract and colorful work, was of being involuntarily swallowed by it. The closer I got, the more engrossed I was in its vibrant colors that seemed to still be dripping in an eternal slow motion. Hypnotizing and calming, Frankenthaler’s color-soaked canvases effortlessly embrace their spectators in light and visual bliss. From then on, I was bewitched, body and soul, and made my way to the next room, the room of the beginning.

Beginnings and Parallelisms

The canvases in this room were all brought together by the very strong presence of Number 14 (1956) by Jackson Pollock. As I stood in the middle of this smaller area, I wondered what Frankenthaler’s experience was like when she saw Pollock’s work for the first time. His black and white composition contrasts with her colorful ones, yes but it does not clash with them. This is particularly evident in Western Dream (1957) with which I would go further as to say that it is an appropriation of the inspiration and lessons she learned from the father of Action Painting. That is, you can see more of what she was to become as an artist than the traces of Pollock's teaching.

The third room is one of the best curated ones in the exhibition. Here, the dialogue between Frankenthaler's paintings and her artist’s friends' work become evident. In the composition of her Tutti-Frutti (1966) you can see reflected the structure of David Smith’s sculpture Untitled (Zig VI) (1965). Or vice versa, in Anne Truitt’s all too white Seed (1969), that blends and almost disappears against the white walls of the gallery, you can distinguish Hellen’s Cape (Provincetown) (1964) where the multilayered and wobbly verticality of her composition unveils the same intention of ambiguity as Anne’s almost invisible column. This intense dialogue between masterpieces prepares the visitor to the upcoming three rooms which only display works by other artists. The internal narrative rhythm is suddenly but subtly interrupted and a distracted visitor might only notice this change only half way through. But despite presenting other artist’s work, they are all still talking about Frankenthaler. These works are either dedicated to her, were part of her personal collection, or were even created in her company, such as Summertime in Italy (1960) by her first husband Rober Motherwell. This cut in the rhythm of the exhibition can be interpreted as a parallelism between the cut that occurred in Frankenthaler’s life, that is, her divorce from Motherwell. After dwelling in these dimly lit rooms, immersed in the works of others that spoke deeply to Frankenthaler, we are led into a room full of light and color, full of new life. After her divorce, she spent less time in New York and bought a home in Shippan Point from where she had a view of Long Island Sound. This serene and tranquil seascape, where she could see and hear the calm movements of nature, became her most faithful companion. The new color scapes she painted during this period, reflect how the changes in her life affected directly her artistic language. Her compositions are less fragmented, the colors, such as in Ocean Drive (1974), more solid, less fluid. They form, in my opinion, already part of the new genre she contributed to create: the Color Field paintings.

Traversing The Threshold Towards Masterful Artistry

As I approached the end of the exhibition, I could feel I was maturing alongside Frankenthaler herself and this feeling reached its peak in my favorite room of the show. I believe the previous canvases were of genius exploration, but the ones in this room are those where Helen painted that something she found during her artistic exploration. Throughout this period, she was influenced by her admiration, not so much of her contemporary fellow artists but mostly by the great masters such as Velazquéz, Rembrandt and Titian. She was an artist that had been perfecting the technique of layering colors, and she achieved unprecedented profundity during this period. I have to admit my opinion on this room is not completely objective, since here are my favorite paintings, but I can without a doubt say that Star Gazing (1989) and Eastern Light (1982) are achievements without precedents in her career.

There is a new depth in her art and it is, in my opinion, achieved through the study of the methods of the great artists, more specifically the glazing technique1. This provided Frankenthaler with the techné2 she needed to step beyond a technical threshold only great artists manage to cross. The deep blues and the almost smokey whites of Star Gazing (1989), or her pinkish black and coppery light orange in Eastern Light (1982) are no longer watery colors dripping one unto the other, blending with masterful control. No, these colors are more than colors, they are veils, veils of time, diaphanous layers of whispers that left their traces in the canvases. These colors are what the great masters whispered to Frankenthaler, they are representations of the sedimentation of prefigurations that transformed Frankenthaler’s initial artistic intention into innovation. When, through these colorful veils, she steps through the threshold of masterful artistry, the initial free intention that pushed her young self to create is transformed into innovation or, as the great Paul Ricœur3 would say, into productive imagination. From this moment on, Helen’s works are no longer only ambiguous, they are no longer only the result of unruled experimentation, they are reconfigurations of this world. However, let's not forget that the world is at the same time reconfiguring Frankenthaler and in this circular motion where she now finds herself, she will begin a search for beauty only perceivable from this dialectic sway of the veils of sedimentation and innovation.

An Endless End

As I left this room, I soon entered what seemed to be a new dimension. During the 90’s Frankenthaler developed two different ways of painting: one, a mighty session where she finished a painting in one go and only added small details later, and the other, slower method where she “worked more” the painting and the results were more “dense”. These two techniques are shown in this room by displaying the different works facing each other. But what truly transforms this section is the sound coming from the room next door. The voice of Frankenthaler, like a siren’s song, draws everyone to the darker room behind a two and a half meters black and white photograph of the artist that decorates this section. Behind the photo, a video of a series of interviews with the artist is playing in loop. As I sat down I truly saw her, for the first time. Her voice played over videos of her painting. The dim lights and closeness of this room made the watching of the video an intimate experience. As Frankenthaler was on the floor, pouring a thin and watery paint substance on her large canvases, we all were there with her as well. She spreaded the paint with a sponge and I suddenly realized she did not use a brush as I was expecting. She achieved the lighter colors not by adding lighter color paint but by absorbing the excess of paint. For the first time I realized that, when she talked about painting with “no rules”, she meant it. Not only did her conception of composition not follow the standards, but also she had “no rules” when it came to the method itself. Everything you would expect her to do to paint, she did the opposite. At this point, it’s safe to say that when she kneeled in front or over her canvas, she did not only pour paint onto it, she poured herself into it.

After the video finished, I stepped once more into the light of the final room of the exhibition. This one is dedicated to the final years of her artistic journey. The paintings here embody the depth she discovered in the innovation of her great masters period, as well as the two different techniques she used in the 90’s. Both are strong and ambiguous characteristics of this final period. With this truth assimilated, she embarked on an introspective and perhaps lonely search for beauty. Younger artists, despite acknowledging her importance in the art world, criticized her for not having “evolved”. They qualified her art as “obsolete and meaningless” while they deemed it more relevant and important an art that was politically and socially involved. I believe Frankenthaler was not oblivious to what was happening during the first years of the new millennium. On the contrary, I believe she was so conscious of the changes and tragedies of these years, and the years to come, that she decided the best way to reflect on them, to bestow something meaningful among the chaos, was through beauty.

The reconfiguration—not a political commentary—of the world through beauty is what Frankenthaler chose to paint during her final active years. In Borrowed Dream (1992) she leaves a turquoise seemingly empty space that is surrounded by this dark, thick red that spreads across the rest of the canvas. And beneath this dark red some scratches let us see an almost pastel yellow hiding beneath it. These whispers of yellow and the turquoise emptiness in the middle leave space for imagination among the red storm that threatens to take over the canvas at any moment. We are unsure if the turquoise is slowly pushing the red away or if the red is bit by bit taking over the turquoise. Frankenthaler does not give us a hint of what is actually happening, she simply paints a moment, an eternal moment of ambiguity. This happens again in Driving East (2002) only this painting is, in my opinion, the most poetic of them all.

This is one of her last paintings on canvas and, without a doubt, one of the most beautiful. The far away horizon, placed at the bottom of the painting, seems to be slowly fading away. The stormy sky above it is heavily pressing down on it and the green mountains below it are unwavering, solid. But behind these mountains, a faint light rears in and some slightly blue clouds appear towards the left, as if challenging the gray above it. This soft light is the element of imaginative ambiguity, not the lack of figurative elements, not the blurry abstract colors, but the dim light that opens up the composition and cuts deep into our interpretation. Thus the horizon unveiled itself as more than an element of a landscape, it reveals itself as an endless end. A horizon is forever unreachable, and Frankenthaler’s painting captures this since, despite the title suggesting movement (“driving”), we are not sure if we are moving towards the horizon or driving away from it. And that is beauty for an artist, an unreachable horizon, ever present in their creations but ungraspable in its entirety, always fleeting, always changing and unruled. Despite our desperate intention to reach those mountains, behind which I’m sure is the answer to the eternal questions “What is beauty?”, neither us nor Frankenthaler can reach it. But it’s only the true artists who can reconfigure the world, the esplanades of our experiences and the self, to unveil the light that enlightens human experience and render possible the knowledge of the unfathomable through the sensible incompleteness of the innovative act of creation.

Notes: