The Shape of Thinking

Felice Grodin’s drawings trace thought at the edge of language.

What if drawing could function the way thinking does—looping, stalling, circling back on itself, often before language takes hold? In the exhibition Where Do I Go From Here?, artist Felice Grodin approaches drawing as a form of mental cartography. Trained as an architect, she treats the page as a spatial problem: how thought moves through uncertainty, how memory and speculation overlap, and how structure can emerge without prescribing meaning. Her ink drawings on mylar are meticulous yet porous, hovering between map and diagram. Her work operates at the limits of explanation, echoing Wittgenstein’s understanding of where language gives way to experience: when words fall short, Grodin turns to marks instead.

Lines assemble into circles and arcs, suggesting systems without fixed destinations. The works feel architectural in their precision, yet they resist inhabitation in any conventional sense. They propose worlds that resemble maps, cities, or landscapes, but remain resolutely psychological: spaces shaped by attention rather than geography. Grodin’s drawings behave like thinking itself: recursive, provisional, and resistant to closure.

Several works unfold through a calibrated tension between control and openness, where precision gives way to interruption. In light language_dark matter (2024), made during Grodin’s residency at the Hollywood Art and Culture Center, marks accumulate without settling into legibility. What emerges is not a language to be read but a system that suggests structure without delivering syntax. The viewer senses coherence without access, encountering a form of cognition that resists translation while remaining insistently present.

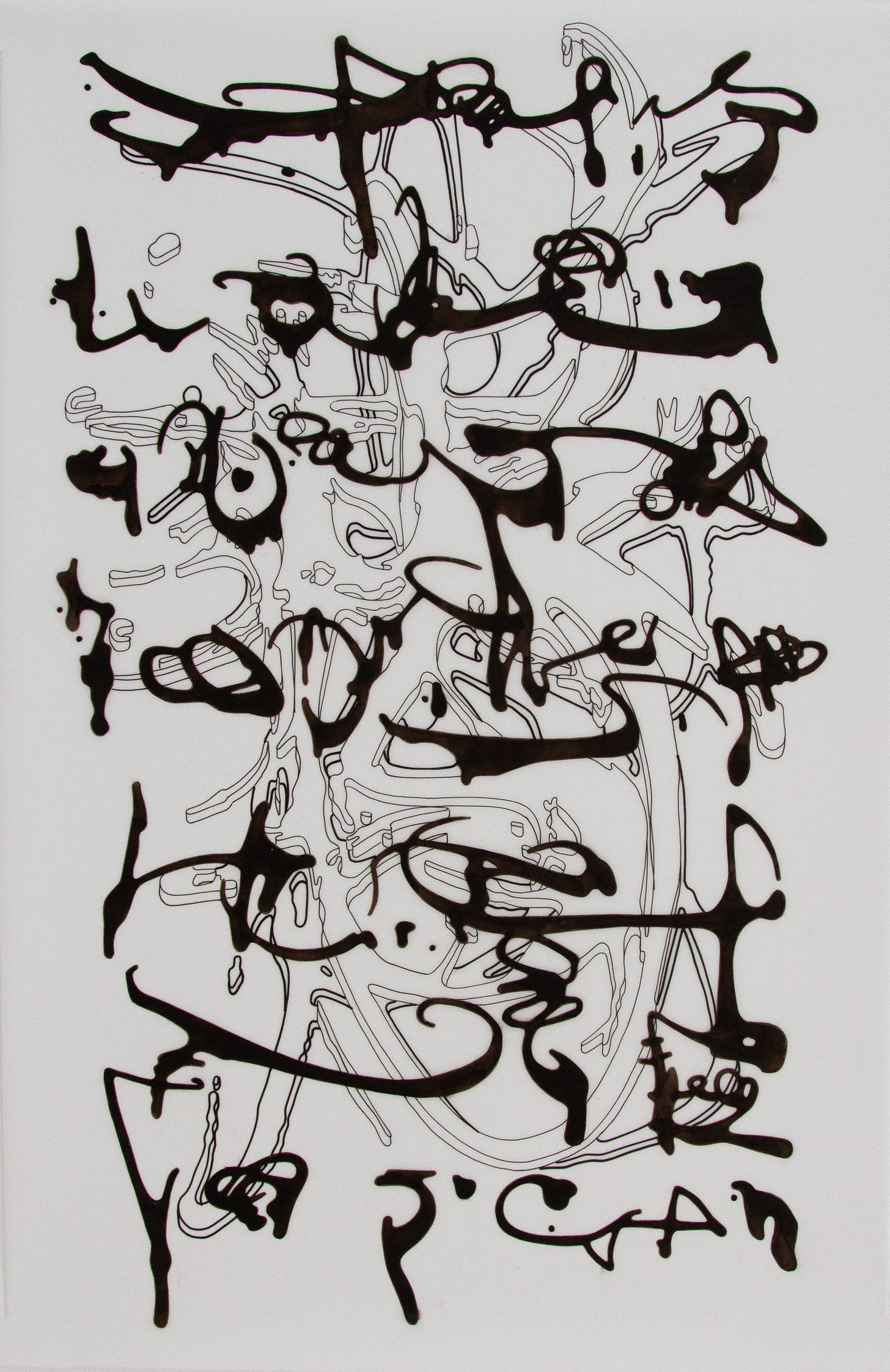

One small drawing, surreal tongue (2024), brings these questions into especially sharp focus. Composed of freehand ink marks on mylar, the work carries the visual cadence of an alphabet without resolving into readable script. Lines thicken and taper like letters caught mid-utterance, stacking vertically as if attempting syntax while continually undoing it. The scale encourages intimacy, drawing the viewer close, where the marks oscillate between writing and drawing, intention and impulse. What emerges is not language as communication, but language as gesture: thought briefly held before meaning settles.

As Grodin reflects, “I’m not sure where meaning properly happens in the making of art, whether it exists before perception or only afterward. For me, the work begins in a sensory, meditative state, connected to something beyond narrative. Naming usually comes later.” Meaning, here, is not embedded but emergent; formed through proximity, duration, and attention rather than decoding.

In toroidal universe (2025), Grodin expands her inquiry into a more explicitly spatial register. The drawing unfolds symmetrically from a dense central axis, its mirrored forms radiating outward in controlled repetition. Electric blues and blacks anchor the composition, while finer linear tracings disperse across the surface, suggesting movement held in suspension. The work reads less as an image than as a system—centrifugal yet contained—where balance, interruption, and recurrence coexist. At this scale, the drawing functions as a diagram not of a place, but of circulation itself, tracing how thought loops, doubles back, and reorganizes without fixed orientation.

In Rorschach transmutation (2025), Grodin turns decisively toward projection. Referencing Hermann Rorschach’s inkblot tests, the drawings redirect attention away from interpretation and toward projection. Forms resist stabilization, offering no hierarchy or legible structure to hold on to. What comes into focus is the viewer’s own act of seeing, where meaning gathers or disperses not in the image itself but in the conditions of perception.

Augmented reality elements extend these inquiries into three dimensions, heightening emotional response while underscoring Grodin’s fluency across analog and technological modes. The exhibition’s center of gravity, however, remains drawing: the hand following thought as it takes shape.

Grodin’s drawings are not texts to be decoded but terrains to be entered, apprehended sensorially before they are understood, as Maurice Merleau-Ponty would have it: where perception precedes language. Where Do I Go From Here? offers no resolution to its title’s question. Instead, it sustains the conditions of not knowing, inviting thought to move, pause, and reorient without the pressure to arrive.

Fascinating article Carmen. Where can I see her work?

so raw!!