Looking for ways to see

Artist Jeanne Jaffe on preverbal images and how we make sense of the world before we have language.

Who among us has not taken a selfie? And what is it that we see when we look at it? And what is it that other people see when they look at that image of us? Social media has offered new tools of self-expression, but staging and comparing has proven to hinder more than enhance our relation with self.

Who am I? Such puzzling questions have no simple answers. Psychoanalysis, a relatively new set of theories and therapeutic techniques, has delved into the subject and offered tools many, artists included, have embraced. Self-knowledge is something artists are very concerned with and psychoanalysis invites one to work through oneself to try and take charge of one’s own desires. It also encourages individuals to sit with discomfort and embrace messiness. And this messiness can become a condition and source of energy that artists can use.

Art and psychoanalysis have had a long relationship. The Centre Pompidou-Metz in France recently closed an exhibition called Lacan, the exhibition. When art meets psychoanalysis, the first time the links between Jacques Lacan (1901-1981) and art are highlighted in a museum space. Before Lacan got his training in psychoanalysis (which wasn’t until his 50s), he had close relationships with André Breton, Salvador Dalí, and many of the Surrealists of the time, that informed his intellectual history.

Lacan is especially appealing also because, in the words of psychoanalyst Jamieson Webster, “he takes psychoanalysis and pushes it in the direction of questions about surface and form and different ways of conceiving space.”(1)

An artwork can be a self-expression and something that transcends the self when it connects with others. Jaffe's exploration and visual vocabulary has opened up ways in which to see ourselves in different perspectives, which connected with both of us. It was in that space between experience and definition that we decided to find out more about her work.

Rina Gitlin: What is your work concerned with?

Jeanne Jaffe: My work is concerned with how identity is formed, and how we become who we are. I look at that from many perspectives through time: from when we’re born and our pre-verbal bodily experiences to when we're introduced to culture and language and social conditioning. I think what has been left out in western traditions, because it has been based on acquiring knowledge, is other ways of knowing and being outside of logic, thought, and scientific knowledge. A lot of my work is trying to get people to return inward; it is about preverbal images and how we make sense of the world before we have language and through our senses, intuitions, and nervous systems. Once we have language, we name things; and once we name things we stop experiencing them, they become utilitarian and fixed. So intuition, imagination, metaphor, associations, all of those ways of knowing and experiencing the world get left behind.

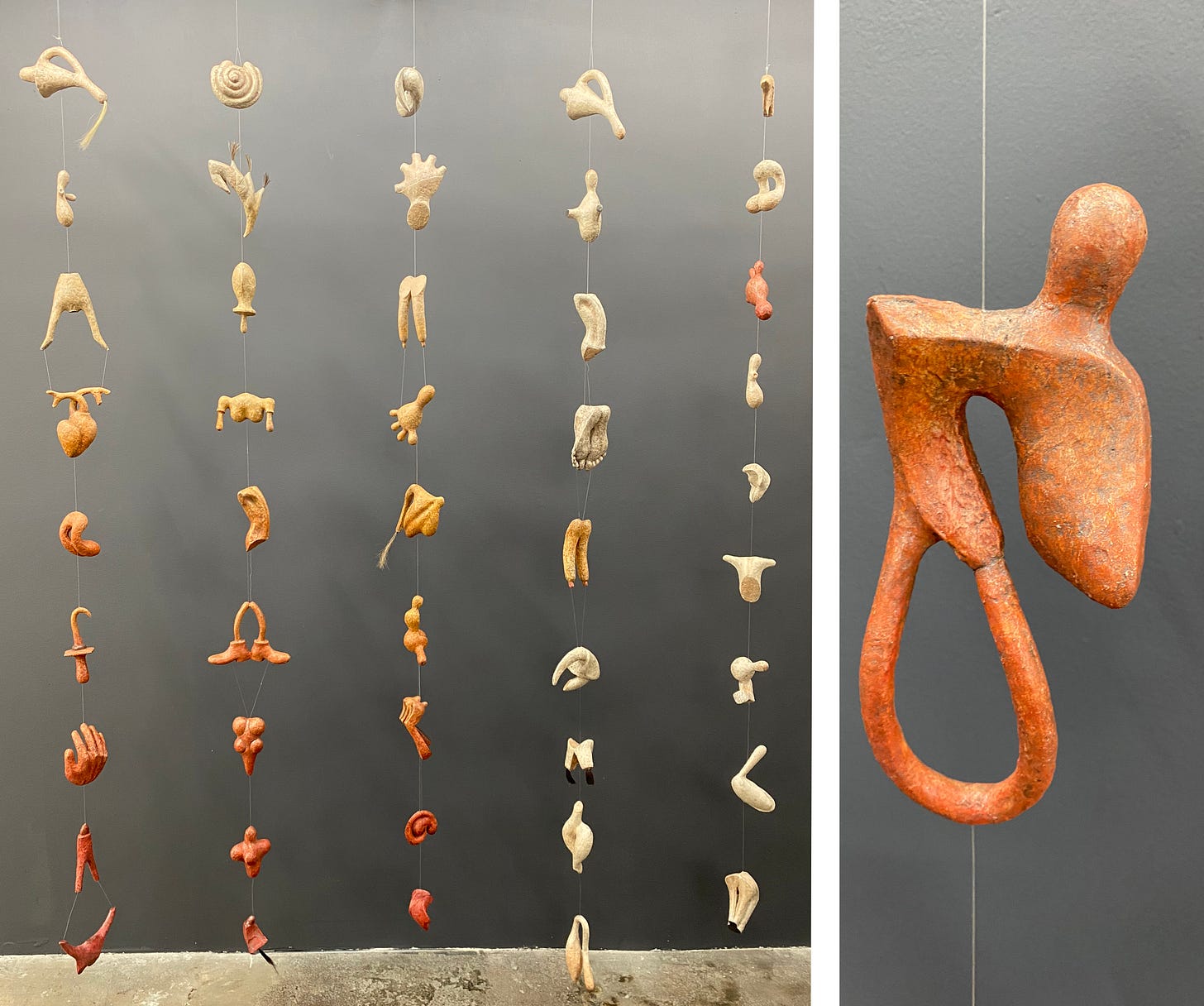

The early work dealt with how a viewer could be reintroduced to their own interior experiences and language through looking at artwork that is hybrid and fluid in terms of definitions. Then I moved on to what happens when we enter language. I'm interested in re-examining the stories we're told so we can regain our own agency, and not be controlled by what culture and others tell us we should feel, think, or be. I'm interested in what is experience, a real experience, not a role we play. And the most immediate form of knowing is through our own senses, through sound and touch nervous systems and intuitions.

Carmen de Terenzio: In your statement you say that you are, “Inspired by an interest in anthropology, mythology, and psychology, my work explores how identity is forged from early, pre-verbal bodily experience through the later influences of language and culture. This is undertaken by investigating the use of metaphor and reexamining our cultural myths and stories.” In what ways do you use metaphor and the reexamination of cultural myths and stories to delve into the process of identity formation from pre-verbal experiences to cultural influences?

JJ: If you think about how we begin to make sense of things, for example, when you look at your hand as a child, before you know it's a hand, you see it has these five protrusions, that it moves, that it can be held up and down. And you see things in the world that you associate with it, maybe in animals or in objects (gloves). Melanie Klein talks about this in her Object Relations Theory (2). She says that very early on, before we look in a mirror, we sense ourselves in parts. The mirror stage is when you actually come to identify a sense of unity. And before that, what Jacques Lacan describes as the sense of the real, or the real stage (3) is experience that is outside and beyond language, stuff you cannot put into words like your intuition, for example: you sense it, but it's beyond language and too complex to reduce to language.

In the symbolic stage you come into the use of language and culture that begins to organize and define everything for you. Lacan talks about language as being a double-edged sword: on the one hand it allows us to discuss that, and on the other it alienates us from our own belief in our experiences or even access to them. So, if you follow that logic, the stories that we are told also contribute, after the imaginary stage, to who we think we have to be, whether it be gender, race or even history.

So by looking at the stories and myths that were told and reexamining and retelling them from a new perspective gives us agency, because I think one of the things we've been conditioned to lose is agency.

RG: Psychoanalysis was embraced by the Surrealists and contemporary artists such as, for example, Louis Bourgeois. You mention Jaques Lacan, Carl Jung and Melanie Klein as being influential in your thinking. How has psychoanalysis impacted your practice?

JJ: I had to go through my own self-examination, trying to understand who I am, how I've become who I've become, which choices I make so that I can choose not just who I've been conditioned to be, but who I wanna be.

RG: It gave you more options?

Yes. If you look at it from a Freudian point of view then it would be reductionistic. But if you look at it from a Jungian point of view, it's transformational.

So there's all those levels in-between. There's something now called internal family systems where you're looking at the multiple voices that are both personal and cultural, all of which make up the psyche, and which we all battle with. I'm interested in exploring those, and I spend a lot of time doing that.

At a young age a sequence of events led me to a certain sensibility that allowed me to be aware of what was happening inside myself, and I would make drawings which would help me. So the self-examination and studying all of this and understanding how this happens was very helpful. Not just to me, this could be applied to everybody. It made me split from what was expected of me.

CT: The Theory of the Dérive is a concept developed by the French philosopher and member of the Situationist International, Guy Debord, in the mid-20th century. It is a method for exploring urban environments in a playful and unplanned manner, aiming to break free from the constraints of routine and the predetermined paths dictated by societal norms. His theory is a playful and critical examination of urban life, designed to understand and subvert the psychological impacts of modern environments. It encourages looking beyond the superficial layers of cities to understand deeper societal structures and forces. So it’s interesting because it’s something that occurs outside oneself but similar to what you were saying before. Could we align your investigations and work with his theory?

JJ: I don't know enough about his work, and I want you to send me that because that is extremely interesting. I've been reading a book called Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything, by Graham Harman (Pelican, 2018). It's a new direction in philosophy where it doesn't just give consciousness to humans, it gives consciousness to everything and speaks on how everything is really energy.

CT: The idea of the Theory of the Dérive is that you interact with your environment, with your city. You go to a park and you don’t do anything, you just stand there and see what happens, how the environment interacts with you.

JJ: I like that a lot. But to me that’s related to religious practice, to meditation, to stopping the thoughts and just sitting and enhancing the other senses; being not being, being not, being nothing. It's related and that's why I'm interested in it.

CT: What kind of impact do you think that can have?

JJ: It gives you agency and freedom. If you look at what's happening in culture today, it's people endlessly just doing what they think is going to “give them success and meaning”, rather than examining what would actually give them a sense of fullness and meaning in their life. So the only way to get off that track is to stop and to allow other things that aren't already predetermined to come in.

RG: Your stop-motion film Alice in Dystopia (a favorite of mine) speaks about how Alice confronts who she is and has to adapt to changes that come fast without being sure of their outcome. It speaks of flexibility of identity and of the importance of discomfort, of allowing oneself not to know because that is where change comes from. How important do you think it is for an artist, or anyone else for that matter, to adapt to changes?

JJ: I think it's super important. It means you think about the consequences of the changes, both positive and negative, which is something our own value system doesn’t encourage. The experience of discomfort is a big part of it. I think we have been conditioned not to want to be uncomfortable. We want things that we're familiar with, we want things that make us feel good. There's nothing wrong with some of that, but it won't create change and growth. I know that the things that have helped me grow have been uncomfortable, and that's the only way real shift happens.

If you look at it historically, it's the same thing. Revolutions occur because people are uncomfortable. Now, if you have a culture that wants to avoid it, then you have the people in power deciding everything and a population that just goes along with it. And that's a problem because to me, it's not a life.

It goes back to the Greeks: The unexamined life is not worth living, and Know thyself, are things that people have thought about forever and ever. And then we became science oriented, which has allowed us to accomplish great things but has done some damage. I mean, just think of nuclear power, and how it could destroy the world!

RG: Meaning we are exactly where we should be because our trajectory in history has been one of confrontation and dominance. It's very masculine. Perhaps we need a shift?

JJ: Which is part of what this work is about: going from a masculine to a much more feminine vision and attitude.

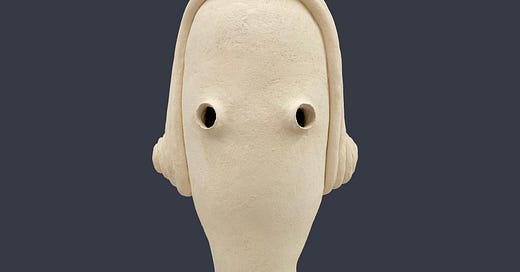

CT: Your participatory works, those sculptures we can look through, invite us to step into someone else’s shoes and see the world as they do and even perhaps to see ourselves through the eyes of others, both related to ideas of vulnerability and empathy. Many believe that if the world will change, empathy will be a big part of it. Could we say that empathy is the lifeblood of creativity?

JJ: I not only think it's the lifeblood of art, I think it's the lifeblood of being alive. I really feel that's where we've lost.

CT: Do you think your trajectory has brought you to a place where you can now share your knowledge and findings?

JJ: Yes. I was scared to share it before. I feel it's outside of the norm in terms of what people really care about, but I feel that's all I care about. I think about how am I gonna feel about my life on my deathbed? I do not want to have lived a life that I was told I needed to live that wasn't my life because at that point, there’s nothing you can do. It's too late, and that's a lost life. That's the way I make decisions. I make decisions based on how they will feel at the end of life.

RG: If you are going to regret it or not?

JJ: Yes. How am I gonna feel about my life if I do this? I think if you don't do that you really haven't claimed your own life, and that's all we're here for. You just don't get a second chance. What's interesting to me is I feel it as a guide. It allows me to tap into what I really care about. Remember when we were talking about those multiple voices that we all carry? Some are cultural. Some are our own. Frequently we can't even differentiate them. So it allows me to begin to hear what I care about and not what I'm told I should be.

CT: That's beautiful, Jeanne. Perhaps that should be part of your statement as well.

RG: Bodies are fragmented in your work. Is it one way of steering away from intellectual and aesthetic ideals of wholeness?

JJ: That's an interesting question. I've never thought about that. I think it's more about sensation of what it feels like to be in a body.

Our idea about the whole body is visual. I see a body, so I say that’s a body. And artistically I would do the whole body. But that's not really my experience. My experience might be looking in your eyes or focusing on certain things, and also knowing what's inside my body. What are the things that trigger things in me, like the heart, the lungs, the brain. What do they look like? So that's the body, not the external one. Our vision is a distance sensation. Touch is not distant. Touch is very immediate. It goes right into the body. As does sound. So there are different ways of experiencing things, and to me sight is just related to language. You see kids looking at their feet or hands and they don’t quite know what they are yet.

RG: Right, they are exploring.

JJ: Exactly, things they can actually see. It takes a while before they realize: that's me. And so that's the beginning of the identity issue that we build over time. It’s massive.

CT: You just had a wonderful survey of your work exhibited at a local gallery. How was it to have organized and seen 20 years of work together in one space?

JJ: I was very grateful to have had the opportunity to show all the work together and to see the rich and consistent dialogue. I also was surprised by the imagination and playfulness in much of the work and how it evoked a magical sense of other worlds. I also was able to see my own exploration of an interest in pre-verbal language and into culture, literature, history, and storytelling: from something very internal and private to something more communal. It became clear I was mapping and trying to understand how we develop and create meaning.