Listening as a form of resistance

Tania Candiani: where individual voices meet collective activism, and the many words that shape 'we'.

What does your work sound like? My work is the intermittent tapping of keys, marking the rhythm of my thoughts. They quietly speed along for a few minutes before stopping abruptly, as if interrupted by something unexpected. In truth, it’s a deep pause—a silence filled with thought, or perhaps the space between thoughts. I wonder what that would sound like.

Tania Candiani, a Mexican interdisciplinary artist, works with an expanded idea of translation across visual, textual, sound, and symbolic forms. She uses it to uncover new perspectives, often drawing on archives and historical narratives for inspiration. She believes art should amplify collective voices rather than individual ones, and her work often addresses communal issues like labor and the feminine condition.

Candiani describes her pieces as translations of the sounds she hears and interprets them across various mediums and languages. This process embodies the idea of faith as a bell that has not yet been rung—a quiet potential reflecting the deep listening central to her work. For Candiani, listening is an act of generosity, allowing for connection and understanding.

Shortly after our conversation, I came across a quote by Cuban artist Glenda León while visiting a local museum:

True listening, that in which we empty ourselves of thought and ego, to let in the words, the presence of the other, is something bizarre nowadays. In a world of so much hurry, so much stress, so much disconnection of man within himself, there is an increasing blindness, and also deafness.

By making us more aware of the sounds around us, Candiani reminds us of the importance of listening as an active, conscious choice. This choice fosters connection and understanding in a world increasingly characterized by noise and distraction. Let’s listen to her!

Carmen: One of the central interests of your work is the expanded idea of translation, extended to the experimental field through the use of visual, sound, textual and symbolical languages. Could we say you translate the present?

Tania: I never thought about that, but it sounds beautiful. It's like a line from a poem: 'translating the present.' But I'm more of an interpreter. I love language, just like you do. I enjoy finding ways to read stories from different points of view. This idea of something that can be understood from multiple perspectives is the kind of translation I'm always thinking about and practicing.

For example, with different technologies or devices invented to help us understand things, I believe that looking at the same technology from a different perspective could lead to new discoveries connected to it. That question fascinates me. I'm using translation to uncover something new, but not about the present—because the present is here and now, and there isn't enough distance. That's probably why I always hold on to archives or stories from the past

CT: Suzanne Lacy provides a framework for conceptualizing feminist activist art in a letter to Patricia Hills, editor of the anthology Modern Art in the USA: Issues and Controversies of the 20th Century. Lacy asks, “How can we work as artists on a broader scale, to create change that will penetrate and affect the institutions, public spaces, and political processes that make up our public culture”?

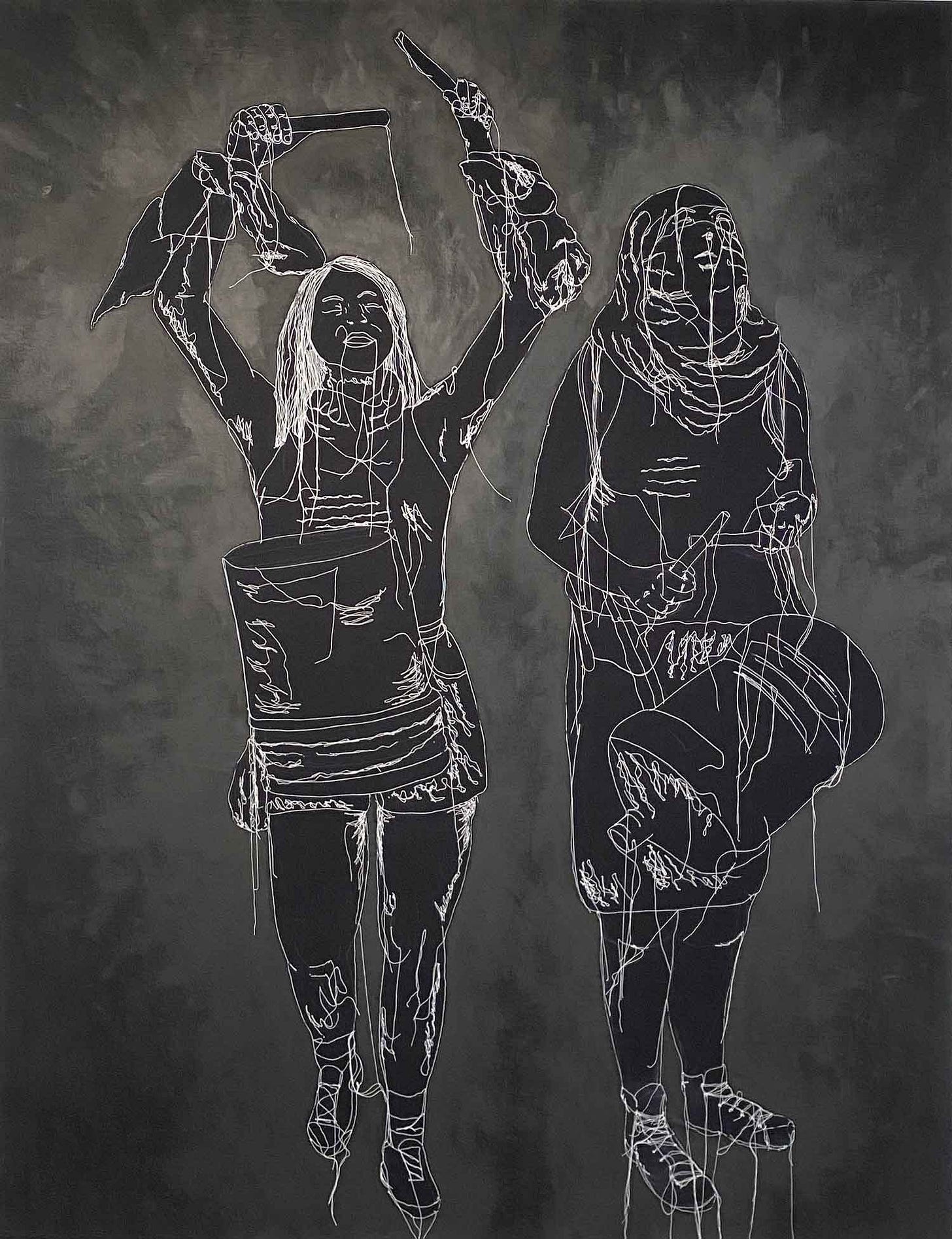

A fundamental part of your work is related to feminist policies and practices, understanding them as a communal, affective and ritual experience. Lacy’s question places a tall order on artists, however I believe your practice bridges theory and practice and addresses her question. Works like Manifestantes (2019) or Gordas (2002), being but a few examples. Could you comment on Lacy's statement? Could we identify a feminist thread running throughout your work?

TC: I know Suzanne Lacy’s work and think what she says is really important: it’s not just about creating from an individual perspective; you need to consider how your work can touch others collectively. When you work with others, you have to expand your voice into a shared voice, one that needs to be heard. If you install your work in museums, for example, that community voice will be amplified. It's not about your voice alone, but about all of our voices. We are speaking as 'we,' not 'I.' From that perspective, we need to be heard through these works. It's a way to bring forward what must be discussed within institutions or in the broader context of society.

I am not a politician; I am a storyteller. I like to tell the stories of others, not my own. There are many words woven into this idea of 'we': how we think, how we feel, our bodies, especially our bodies as women.

We are also 'we' in the subway, feeling uncomfortable because there are only two cars on each train dedicated to women passengers, a policy put in place because women have been harassed in the past. Instead of changing policies and educating the public to be respectful, we have policies that are offensive and ineffective.

So, there are many areas where Suzanne Lacy's statement is significant: being part of a collective is a political way of living.

CT: I admire your work so much because you choose stories that show political awareness of where you are. You are making a lot of noise with the drums in Pulse (1), for example. It’s very powerful, like a wake up call. Your work with sound rose to a crescendo.

TC: Yes. I would like to talk about the connection that exists between Manifestantes, Gordas and Pulse, the three pieces you named.

Gordas, an exhibition in Tijuana (2002), was my first big project as an artist. I had read a story in the San Diego newspaper about a new illness, Vigorexia, where people were so obsessed with their body image that they spent long hours at the gym to the point where they were losing their jobs and families. I was just so shocked.

I was also researching magazines dedicated to women. In the US during the war these magazines pushed women outside the house: “You have power, you can work, you are a force of labor”. When the war ended and women needed to come back home, the image of the ideal housewife was put on an altar: there were illustrations of women by laundry machines and in kitchens. Contemporary magazines, on the other hand, told stories of models suffering from eating disorders.

But It was also about myself. I'm always on a diet, it was part of my education. I remember my mom, my aunt and my friends being on a diet all the time. It was under that lens that I started working on the series of Gordas: the body of all of us women

Manifestantes was a series that began in 2019. There was a particularly intense episode in Mexico City, where a group of policemen raped a very young girl. We all took to the streets in protest. During one of these protests, a young woman at the front of the march threw purple glitter on a police officer's face. That image was incredibly powerful. We all rushed out to buy as much purple glitter as we could find. Those protests became known as the 'Glitter Revolution.'

That's when I began working on this series. I felt frustrated, but also empowered by marching alongside all the other women. We were all so angry because the police are supposed to protect us, not violate us. What I like about the process of Manifestantes is that the images come from the press, like a living graphic archive. The poses are strong—stills taken from press coverage and Instagram. Each piece includes the date and location of the march in its title, which is crucial for keeping the moment alive.

When Manifestantes was installed at MUAC - Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (2022) the room was silent, but the images seemed to be shouting. In a way, they were actually louder than any other words I could have used.

CT: Your work frequently engages with themes of labor, examining its cultural and social implications through various crafts and industrial processes. How do you approach the relationship between labor and art, and what insights do you hope to convey about the nature and significance of work in your practice?

TC: There’s a beautiful anecdote I always like to share because it marks the moment I began to perceive labor differently. In 2015, I went to Oaxaca (southern Mexico) to work on a project called Chromatica, curated by Blanca de la Torre. We spent a wonderful month there, and I had a few ideas in mind. One was to reenact the process of creating indigo blue within the museum. Another was to create a musical instrument from a manual loom, which required finding a discarded loom.

That’s when I met Fernando, a master weaver. As we toured his workshop and discussed my needs, we discovered our shared interest in sound. He explained that, during the warping process, he works with the lights turned off so if a thread breaks, he can hear it. That moment changed my perception of labor, as I began to see how sound also plays a role in it. He helped me hear the sound of labor. And I found it so beautiful.

That's when I became interested in bringing the sound of labor into a museum setting. For that exhibition, we had a large loom and a weaver actively working throughout the five-month duration of the show. As visitors entered, they were greeted by several videos depicting the weaving processes, accompanied by the sounds of the weaver at work. You could watch him moving in a dance-like rhythm as he worked. The audience was able to be immersed in the beauty of that labor.

After that experience, I began working on other labor processes. I recorded video in India, featuring a group of female construction workers, all dressed in traditional Indian attire, passing heavy buckets to one another in a dance-like motion. It was incredibly beautiful to watch.

In Taller de Confección (Sewing Workshop) two women who are expert balloon makers spend one month creating a balloon at the Museo del Chopo in Mexico City. This concept was inspired by an image I found in an archive showing women making balloons hundreds of years ago.

Sounding Labor, Sounding Bodies was an exhibition I created in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 2020. During my initial research visit, I noticed beautiful mosaics at the airport depicting the city’s prosperous industrial past. When I looked at the original photos the artist used to create these murals, I realized that the women workers who appeared in the photos had been removed from the final pieces. There were about 20 murals representing the city’s major industries, all of them featuring only the male workers. The women had been literally erased.

The project became focused on recovering the stories of these important women workers. In the video piece Four Industries, a female choir “sings” the sounds of machines from the early 1900s. In Working Women, ceramic tiles were created to include the women who had been excluded from the original depictions. These tiles were produced at Rookwood Pottery, an internationally recognized local company founded in 1880 by a woman who trained other women. It was wonderful because present-day women workers were able, through their labor, to restore the presence of those women previously excluded.

CT: In a recent interview, you mentioned that ‘listening is an act of generosity' and ‘a tool for expanding and transforming perception in both human and non-human contexts’. Could you share what you have learned by listening?

TC: An entire world opened up to me, thanks to Mestre Fernando. We are always hearing things, sound waves are physical, they actually touch our bodies. However, there's a difference between hearing randomly and the act of listening: by listening we give our full attention, we are present and recognize the other. And that is generous. I delved deeper into exploring new ways of understanding our capacity to hear and how, through sound, we can communicate and connect with others, even of different species.

In For The Animals, a project that took nearly five years of research, I created experimental sound scores designed as lullabies for the indigenous animals of the Arizona desert.

It all started with my first visit to Phoenix, Arizona. The curator and my friend Julio Morales picked me up at the airport, and as we were driving to the Arizona State University Museum, we passed an incredible rock formation called Hole in the Rock—a large, beautiful red rock with a hole at the top. To me, it looked like a speaker, and my first thought was: "Let's use that rock as a source for amplifying sound."

When we visited the formation we discovered that below it was an open-air zoo with various species native to the Arizona desert. Arizona is both a region that extends into Mexico, and a border with not one, but two walls. Many animals that once migrated freely across the desert now have their paths blocked by these walls. That was an incredible opportunity to talk about both human and non-human migrations.

The idea was to create a sound composition that the different animals of the region would enjoy. So we installed speakers and night vision cameras with face recognition technology trained by artificial intelligence to recognize, for example, the Mexican wolf. When the camera caught its image, its specific melody would play.

In the process of creating this work, I delved into sound ecology and explored how it moves through geological layers. There was sound long before there were beings to hear it; sound has existed forever.

CT: Wittgenstein has conjectured that the limits of our language are the limits of our knowledge. Text has played a central role in some of your works such as La Marcha (2023), and Mattresses Mantras (2004-2011). Do you agree with Wittgenstein’s statement? What is the importance of words, or text in general, in your practice?

TC: I don't agree with his statement. I love words. I was trained in literature and thought I would become a writer. I write all the time. I write scripts for all my videos. There are always words everywhere in my work. We started this conversation talking about translation, not necessarily translation of words or languages but the concept of translation.

To that end, there's another anecdote I’d like to share. I was invited to propose a project for a residency in Gdańsk, Poland. I initially imagined a workshop that would involve creating an atlas of the different neighborhoods, reading several books together, and writing down stories about the city's hidden aspects. Then, the curator informed me that none of the 23 people who had signed up for the workshop spoke English. I thought, "How will I conduct a workshop in Polish, a language I don’t speak?" It turned out to be amazing, though. We found a way to communicate without using words. We walked through different neighborhoods and recorded a silent movie featuring the local ghost stories. They dressed up and performed, bringing those stories to life.

Language as Sound (2015), another project I created there, came to me while riding the tram. The sounds I heard had no meaning to me because I couldn’t understand the language; they were just sounds. I discovered that the Polish language has six sounds that are unique to it. In this piece, six women perform those six distinct sounds, transforming them into a melody without meaning.

The limit of our knowledge isn't defined by our written or spoken language. I’m concerned about the languages that are disappearing. We need to speak those words to keep them alive. In Mexico, there are still 57 languages. Can you believe there's a language in northern Mexico that only three people can speak? So, preserving them is crucial—not in the way he suggested, but because we need to expand our limits and protect what remains.

CT: Your practice is research-based, focusing on the present while also preserving the past, particularly older technologies. Yet, much of art is truly understood in hindsight. In considering how the times we live in might be remembered, how do you think your work will be perceived in the future?

TC: I maintain a well-organized archive for each of my projects. Everything is stored in labeled boxes that provide context for anyone interested in understanding the background of a piece. I have a deep appreciation for archives, and I view them as treasures, especially when they offer insights into the thoughts and intentions of the people I'm researching. In our studio, we have a dedicated room for these archives, and we’re committed to preserving them for the future.

I don’t know how my work will be read in the future. It’s not a reflection of the present and will likely be interpreted in many ways. While I am curious, I don’t really think about this. I’m not an academic or a formally trained artist, and I don’t read art philosophy or art history. Instead, I focus on subjects that interest me, like science. Currently, I’m reading El Clamor de los Bosques (The Overstory) by Richard Powers and Maniac, by Benjamín Labatut.