Leo Castañeda: a conversation

Multimedia artist and video game director Leo Castañeda on creating alternate worlds using mythology as a lens to understand people and nature.

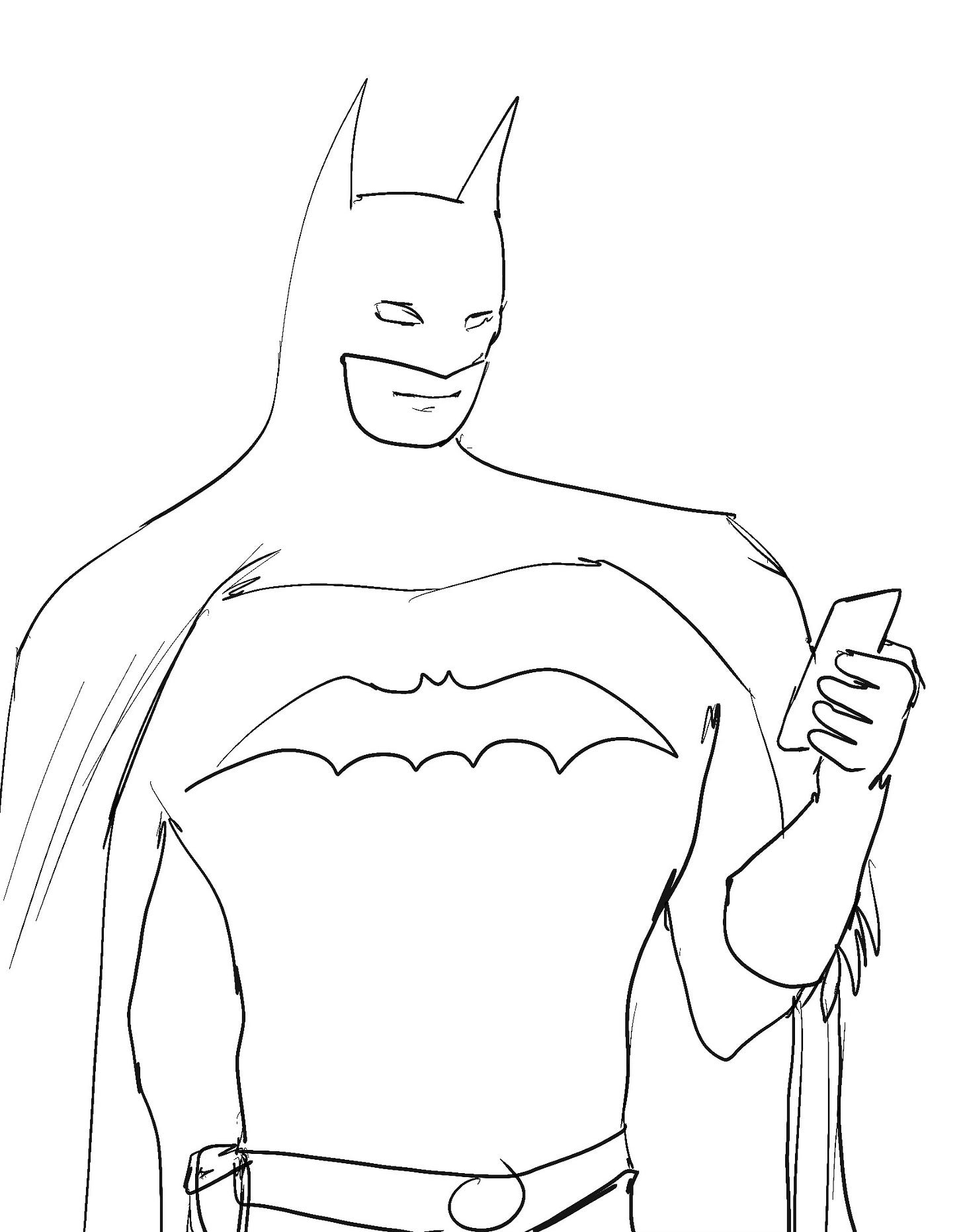

Young children are known not only to have a high tolerance for repetition, but also thrive in it. As a child I would beg my mother to tell us Little Red Riding Hood or Mowgli as many times as she was capable of (truth be told she impersonated characters and sang beautifully). On researching Leo Castañeda’s work ahead of a conversation we had planned, I found out that as a child he would ask his father to draw Batman over and over again. That meant I could skip that inevitable question: Where did it all start?

Leo’s studio (which he shares with artist Lauren Monzón) is spacious and cool, “My first with air conditioning”, he said. Theirs is one of the courtyard studios at The Bakehouse complex, in Miami. The dark gray metal double doors surrounded by bright, energetic yellow walls already suggests the startling world we’re about to enter. The small, white “Studio 55” vinyl sign followed by the names of both artists is minimalist, shy, almost an afterthought.

Leo is a soft spoken artist with a kind disposition and sharp, observant eyes of a deep thinker. I have known him for quite some time and his work has intrigued me for much longer. Recently we got together for a conversation on the interconnectedness of painting and gaming and reimagining beings in a way that is more mutualistic, sustainable and interconnected, the influence of AI and the evolution of gaming.

Carmen: In your statement you describe yourself as “an artist working at the intersection of virtual reality, gaming performance and interactive sculpture,” and that you “deploy and deconstruct the social economic racial mythological and post-human anatomies embedded in the structure of video games.” Could you unpack this definition?

Leo:Thank you, Carmen. That artist's statement is from a few years ago and we’ve been trying to figure out how to make it more accessible. We're looking into how the gaming companies communicate and how to make those concepts be more accessible to people that are not artists.

The mediums that I work with are feedback loops between gaming, painting and drawing which are all interconnected. It's a process where the handmade and digital are interconnected.

The axis of the work, the main video game that I've been working on for many years, is called Levels and Bosses, which is the traditional, antagonist and progression structure of video games where there is some kind of oppositional force you have to defeat after every level, usually through violence. So the game (and the work) is about trying to figure out different, sustainable interaction models that are not necessarily bound on conquering or destroying something or extracting energy in a way that is not mutualistic.

A big part the work is trying to create this alternate world using mythology as a lens to understand people and nature.

CT: What would you say your work is mainly concerned with?

LC: The number one idea is to reimagine beings in a way that is more mutualistic, sustainable and interconnected.

CT: Ok, thank you. I would like to jump to something else. Being the creator of worlds where you reimagine beings that are more mutualistic, sustainable and interconnected, as you just said, you are addressing political and social structures. Would you consider yourself an activist artist?

LC: I don't think I'm an activist artist. When different political events happen I don't feel compelled to voice my opinion online, for example. For me it’s more about listening, learning, internalizing and reinterpreting through my art and adapted behavior. Perhaps, for now, I’m introverted in that way.

CT: If we consider that your main concern is to create beings that have a more mutual understanding in worlds that are more sustainable, that is a clear social and political commentary.

LC: As an artist, I show that through my work and not necessarily through political activism. In a video game you have the ability to choose how to interact. In this video game, you could choose to be destructive or choose to be violent, but it's easier to be more sustainable and mutualistic. That has been one of my challenges.

CT: But you are the one who creates those choices, is that correct?

LC: Yes. The video game has a spectrum of intensities that one connects with. So, for example, you can use the beings in that world to create vibrational fields through their hands that can stabilize the ground. But if you intensify those fields then they destroy it. There's always this spectrum.

CT:That also speaks to one having a certain power within oneself that can be overused, creating a world where you have energy that can be used in different intensities.

LC: Yes. In terms of narrative building, it's been a bit of a challenge because a video game is not an exact linear narrative like a movie or a book. I guess there are some books or movies that have branching pathways, but one of the challenges has been: does one show an ideal or utopian world by just showing it, or does one also show the oppositional force of it?

Actually one of the situations that has been interesting from an art perspective is this new work that is the prologue of the game, this kind of village where these amphibious beings are all around this teleporting machine, and they're dancing and they're taking turns going on the teleporting machine to launch themselves into an explosion. And, the explosion has non-linearly affected them already. It's the source of their energy at the same time.

CT: So it creates and destroys them?

LC: Yes. And they're taking turns to leave everything behind and go and understand that potential. And they're also dancing before it. So it’s the combination of what is good, what is bad, what is dangerous, what is afterlife versus going to just discover new things. I'm enjoying the tension that's happening there, where it's not fully known. They might be beings that can live sustainably with their landscape, but there's still macro climate change situations that are affecting them.

It’s been interesting to try to figure out, as the game and the game worlds evolve, if all beings in that world are just adapting to change in different ways or if they are actually going to be beings that are, I wouldn't say evil, but antagonistic in a very specific way towards others, as when you read a book or see a movie and you can identify that character as representative of jealousy, for example.

CT: The basic formation of this idea that you described is related to our notions of faith, and with ideas of creation and destruction. It seems like this idea that you are transferring into this work is not only a game but also an experiment on other ways of living. Would that be a correct assessment?

LC: Yes, that would be an ideal assessment.

CT: Do you think that neural networks, in the future, could allow creators of video games to let the game evolve as the characters evolve?

LC: Yes. Yes. We're not there yet, but the tools are definitely evolving towards that. And that would be amazing because one of the ideas that games could do better than other media is create an open mythology. There are some video games, like Fortnite for example, that are made with the same program. Fortnite sales allows the company that makes the Unreal Engine, Epic Games, to be free and accessible to artists. Last year Epic Games opened Fortnite to have user generated content so people could just create their own levels. And that's definitely something that I really want to do one day. I would also like to work with other collaborators so I’m not the only designer. I feel like creating a full spectrum of open, varied and deep models for Level and Bosses is beyond my individual comprehension for the game to evolve to its potential.

CT: If you want to evolve from your initial creation, it would have to include other minds?

LC: Yes. And the mind could be an AI. The beings of this world could be future AI beings as well. They don't necessarily have to be human. They could be future sea slugs or robots for example.

I'm definitely interested in what AI's morality is going to be. Will it be just a regurgitation of all the imperfect organizational structures that we have as humans?

CT: So far, yes.

LC: Yes. There was a podcast that I heard with Grimes inquiring whether there would be a way to feed AI stories or mythologies or ways of being that could help it create new models? Maybe it can do that eventually, but on its own, maybe it won’t have our human imperfections that make us kind of destroy the earth while we're progressing.

CT: Do you think, then, that neural networks and AI could be the way that your art and gaming could evolve?

LC: Yes. It's definitely a long conversation with many questions like how AI is affecting art. People are reacting to AI. They’re worried it's going to take their jobs. I think governments and companies are discussing universal basic income, for example.

CT: Yes, I agree. That's a long conversation.

I wanted to ask you one last question. Surrealism is an art movement that interests me immensely. It came about in Europe's interwar years where art felt the need to detach itself from reality and from what was, and look elsewhere for reason and meaning. Surrealism is making a big comeback now. Do you feel its return may be because we’re in a similar situation, having to detach ourselves from a reality that is difficult to grasp and in need to imagine and create alternate worlds?

LC: Yes. AI is coming and it's the biggest scare. It’s seen as the most realistic version of that old fear of aliens landing on our planet and conquering us. So we have basically a God arriving on Earth as we speak.

CT: Do you feel that we create alternate worlds because we don’t know what’s coming?

LC: Yes, and I think climate change is the biggest fear.

CT: Climate instability, economic insecurity, shelter instability.

LC: Yes. And wars.

CT: Wars. Genocides. And then there's AI.

LC: Yes. All happening at the same time. It’s interesting the association with Surrealism. I didn't start working on games because of its influence, or consciously reacting to Surrealism. I think it was because I loved video games and sci-fi.

CT: Do video games and sci-fi always involve creating new worlds?

LC: Yes. And that's one of the things that I've enjoyed about this process: setting up this structure and then being open for life experiences and new knowledge to evolve it. One of the challenges I had in art school (especially in undergraduate school) when I started coming up with this series, was how to make conceptual art that felt genuine and fun; how to make art that felt like fun, that wouldn't feel like something that had to be difficult. I mean, it's very difficult because it takes many hours, and it's been a hard journey to figure out how to make a game and how to learn all the software and put together a small team every once in a while.

Since I was a kid, I have had that childlike wonder after drawing characters like Spider-Man and imagining the story behind them.

The work goes back to that wonder, but informed by conceptual art and the world around us. So it's not just creating another comic book story.

CT: I have one last request. I read that when you were a child you would ask your father to draw you Batman, over and over again. I was wondering if you could draw a Batman for us?