Giving Form to Time

Photographer Luis Paredes' fractured images trace the fragile threads of time and resilience, mapping the landscapes of memory and the future.

What would you do if a fire consumed your life’s work—your archive of photographs, your negatives—reducing years of labor to near destruction? That experience captured in frames, now unrecognizable or gone. This is the tragedy that befell photographer Luis Paredes (b. 1966). He was shattered, yet he couldn’t bring himself to let go. He gathered the remnants, tucked them into boxes, and carried them wherever life took him. Twenty one years have passed since then.

Salvadoran-born and based in Copenhagen, Denmark since 1989, Paredes was diagnosed with leukemia at an early age, a disease he has battled ever since. A longing for a sense of wonder that began in his childhood, when he was mesmerized by math and physics, seeing them as a mysterious language sending messages that needed to be decoded, combined with his experience of illness, has deeply informed both his life and his work.

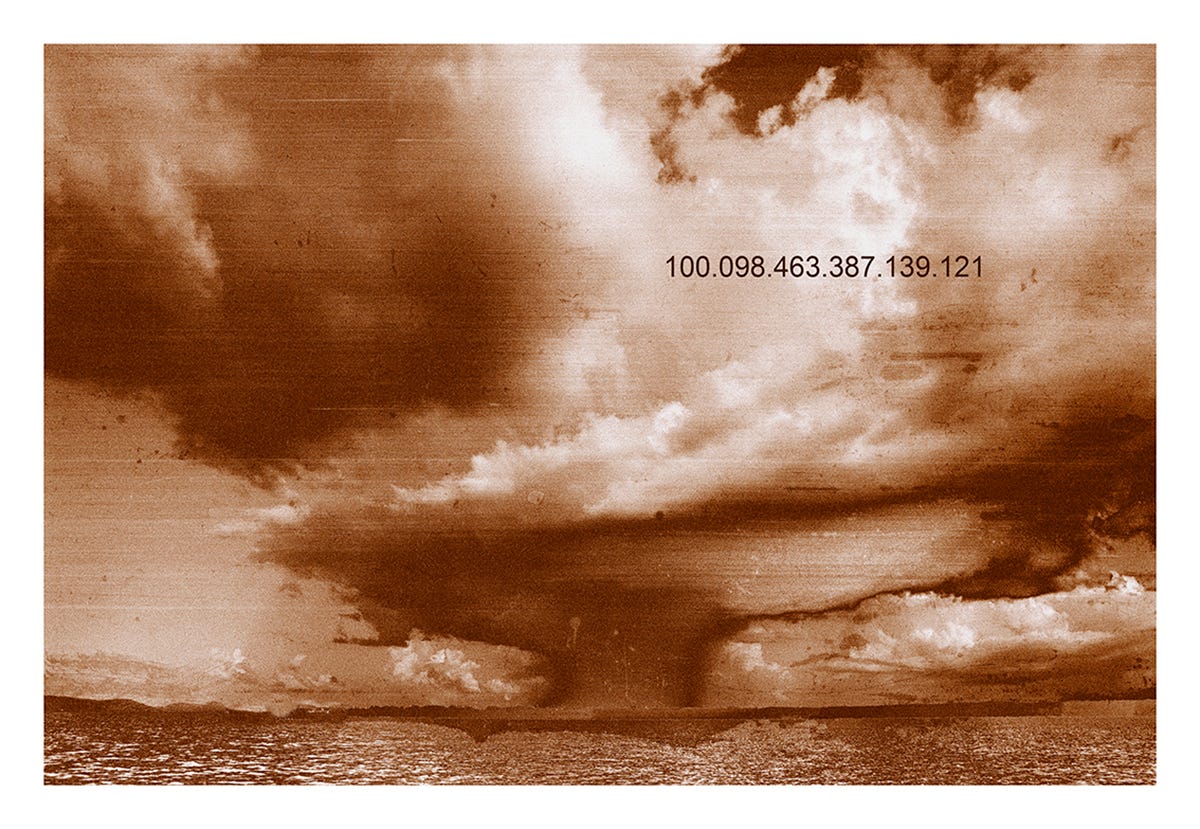

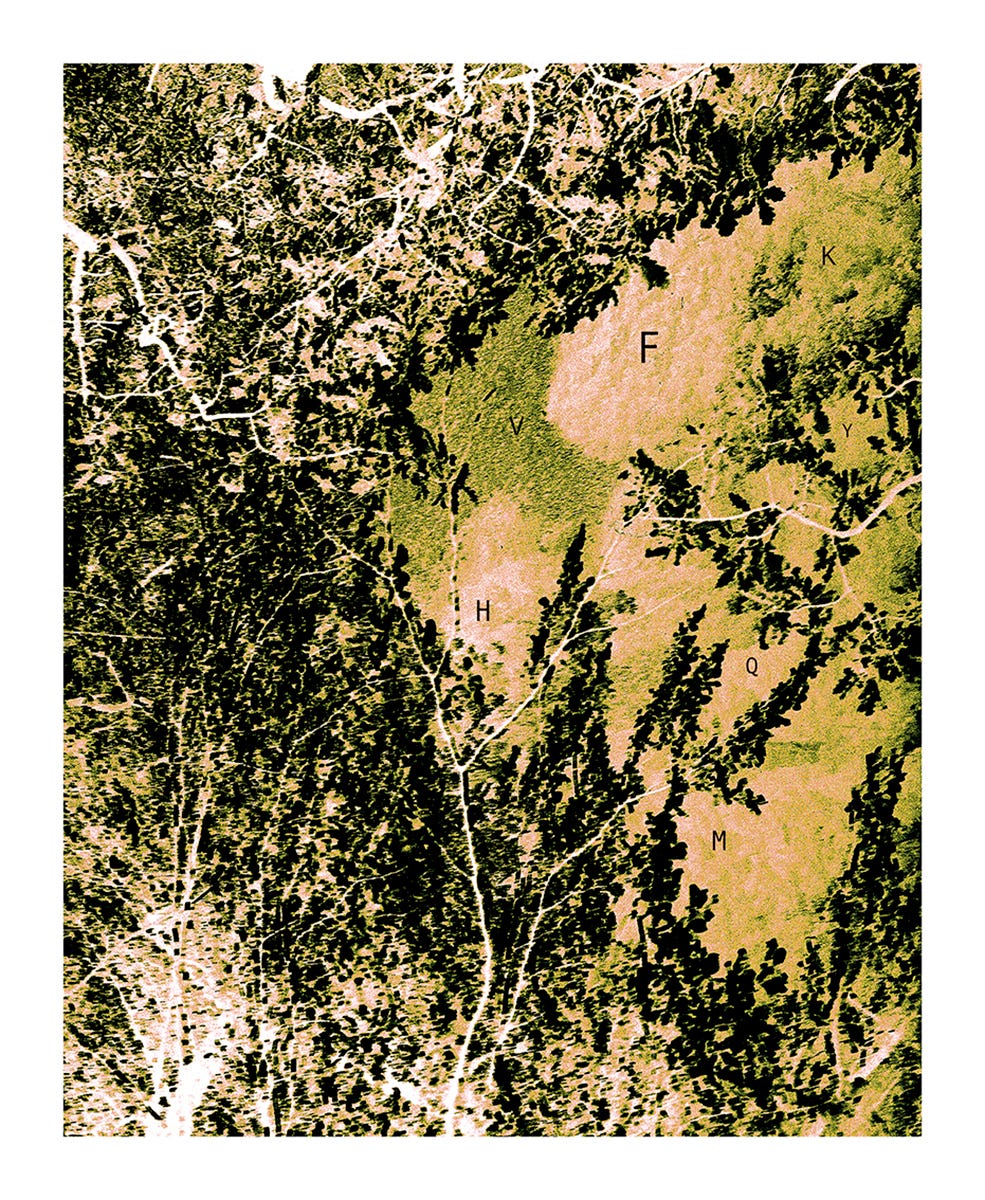

On a sweltering July day, as I walked into a gallery, I had the uncanny feeling that the pages of the book I had been reading had come to life. My summer reading, Benjamin Labatut's When We Cease to Understand the World (2021), a “nonfiction” novel that explores the moral crises of science, blurring the lines between reality and imagination. The images, much like the novel, were haunting yet poetic: a sepia-toned forest with the letters "R," "K," and "F" subtly marked, hinting at hidden narratives within the natural world; a pink-hued sky looming over a glowing, distorted cityscape, punctuated by a floating letter "X" and a silhouetted spear-like object, suggesting a mythic or otherworldly moment suspended in time.

It was during the pandemic and its abundance of stillness that Paredes, like so many, found himself with time to fill. Returning to the fragments of his charred negatives—especially those he calls "photos of horizons"—he noticed something unsettling: their fractured lines mirrored the broken landscape of our present. Inspired, he "wrote" a visual novel, weaving together a series of “short stories”, each tethered by the delicate thread of time, and named them Anthropocene Archives.

Though absent of human figures, the images are imbued with the human gaze, reflecting our curiosity, and perhaps vulnerability. They invite us to wonder: What does photography truly capture—memory, imagination, or the fleeting essence of a moment? Can a photograph, fractured and remade, speak truths its original form could not? To better understand the mind behind these evocative works, I spoke with Luis Paredes.

Carmen: Anthropocene Archives is the title of your latest photo exhibition, which you describe in the accompanying text as 'part of a collection of visual essays exploring themes of the future.' The images are at once striking, incredibly poetic, and sometimes disturbing. Could you tell us how this project came to be and share insights into your process?

Luis: It was a combination of things. I see this series as a collection of short stories with a shared DNA. Each story stands on its own, but together they reveal a common origin.

When I was finishing the series, I started noticing recurring patterns and concepts that connected the photos, even if certain elements were absent in some and present in others. Initially, I was confused about why these kids didn’t look alike, but later, I realized the deeper connections between the images.

The project began during COVID-19, a time that felt like living in a science fiction reality. It was unlike anything I had ever experienced, even after battling leukemia and navigating medical and psychological challenges. This was the first time I questioned whether what I was living through was real. It felt surreal, with echoes of 1984—a strange coexistence of contradictions.

There was a deadly virus, yet there was also rapid scientific progress, like the development of vaccines. I had to get vaccinated early due to my weak immune system. The situation was both protective and unsettling—leaving me feeling cheated and cared for at the same time. It was a schizophrenic reality, confined to my house, with the world outside polluted by this new and unknown virus.

Ten years earlier, there was a fire in my apartment building. My family and I fled without taking anything. Although the firemen stopped the flames, the heat destroyed much of our belongings, including many negatives and my archive. The negatives of horizons I had used for eight years—including at the Venice Biennale—were ruined. It was devastating. I couldn’t bring myself to throw them away, even though they were no longer usable, as they held so much of my past.

I kept the damaged negatives and moved them with me over the years. During COVID, like many others, I was spending a lot of time at home and started doing things I usually didn’t have time for. I opened the boxes and found many negatives melted, distorted, or destroyed. I couldn’t recreate my past work, but I noticed some were landscapes. It struck me that these landscapes, captured as they were 10 years ago, had been transformed by heat and catastrophe.

I realized that’s what’s happening in the world constantly: landscapes are always changing—whether due to catastrophes, human development, or other forces. In case of COVID, I saw it as a catastrophe. It also made me think of global warming and the rapidly changing landscapes of the North Pole. In a way, my negatives had undergone their own small Anthropocene-like experience.

This made me wonder what information remained in those negatives. When I scanned them, I found them beautiful, but also sad—they no longer looked as they once did. I had to accept them as they were now. I even tried to fix them, but I quickly realized it was futile. Restoring them to their original state would have taken ages—it was impossible to bring them back to the past.

I then thought, why not take advantage of the damage and use it to create a new world from what was once in these negatives? That’s when I began adding circles, trying to patch some of the scratches, or using the scratches themselves as a form of expression. When the negatives were bent, I bent them even more.

I started experimenting, and realized that by embracing the damage and even intensifying it, something really interesting emerged. It was a new world—one I couldn’t quite recognize yet, but sensed it could be a glimpse of the future: mathematics, technology, DNA processes, biology, artificial intelligence, robotics, space exploration.

I began to see these images as if they were documents created by archaeologists from the year 3000, examining the remnants of a past civilization—or an extraterrestrial observing Earth, trying to piece together what had happened. As in archaeology, you can never tell the full story, you only have fragments and references. I liked that about these photos, such as the one with the red forest and the RKF letters. The letters reference something, but they don’t explain it. You sense something significant happened there, something ominous, but the mystery remains.

It was as if this archive had been uncovered, leaving you with the question, "What does it reveal?” I kept that ambiguity because I believe it sparks the imagination and allows the work to keep evolving.

CT: When I first visited your exhibition, I was reading Benjamin Labatut's When We Cease to Understand the World (1) and had the uncanny feeling that I was seeing visual evidence of what the book described. In one passage, it states: '...it was mathematics—not nuclear weapons, computers, biological warfare, or our climate Armageddon—that was changing our world to the point where, in a couple of decades at most, we would simply no longer grasp what being human really meant.' (p.187) In another passage, the German astronomer, physicist, and mathematician Karl Schwarzschild (of the Schwarzschild singularity, an early name for what we now know as a black hole) wrote to a friend: 'We have reached the highest point of civilization. All that is left for us is to decay and fall.' Works like The RKF Case, Cosmos, and 100.098.463.387.139.121.2021 especially come to mind as settings for this world described. Could you please comment on these statements.

LP: That’s when I realized you had captured some of the references I wanted to awaken in people—and in myself—through this work and its outcomes. I do believe the work reflects the collapse of a civilization. At the same time, there’s a trace of that civilization in the images, though they’re difficult to understand. There are elements you don’t fully comprehend, yet they still hold a sense of meaning or authority. In the photos, you see letters, circles, and other symbols that might have some logic, but their meaning remains unclear because they’re from a post-apocalyptic world.

I do feel that in those pictures, I’m expressing pivotal moments during or after the collapse—like this one with the long number 100 (100.098.463.387.139.121). You don’t know if it refers to the time of the explosion, or if it’s just a measurement of acidity in the atmosphere. But because it’s recorded, it must be important. It must reference some consequence that followed. The same with The RKF Case: those letters in that part of the landscape tell you that something happened there. And it must be important otherwise why would they be registered?

In a way, I feel the entire series speaks to pivotal moments in history that changed the world. But I see them as if they were discovered in a distant future, like an archaeological find. Imagine someone saying, "We found this document with an image of a red forest and three numbers. What happened there?" Then, as an ecologist or scientist, you’d try to piece it together—maybe it was when oxygen was scarce and everything began to disappear.

CT: There are no human forms. Was that intentional?

LP: Yes it was. I believe it leaves room for imagination because a face—whether familiar or not—becomes a story, even if it’s just a shadow. When I see people in pictures, they seem to land in human narratives, becoming documents of space and time. But you also sense that this world, the one portrayed in the work, is now empty of human life. My imagination placed me between catastrophe and the future, where these remnants existed. Maybe other civilizations tried to make sense of it, or the few survivors used technology to maintain a false reality. Or maybe it’s just the remnants I transformed from my negatives.

I have always been fascinated by the unknown. I prefer mystery over facts. Growing up, I often struggled to understand concepts like square roots and how atoms worked, which led me to believe I was bad at school. I would zone out in class, and when asked to explain something, I’d admit I didn’t know what to do. Though I was distracted, my classmates loved me for entertaining them. I remember seeing a beautiful drawing of atoms and orbits on the board, thinking it held some magical secret, but when the teacher explained it, the magic disappeared—it was just facts and formulas. Once I understood the explanations, I found them easy, even boring, and I realized that while symbols were puzzling, once decoded, everything seemed too simple. I longed for that sense of wonder and mystery, wishing things could be more surprising—like how I once imagined math could have different answers every day: two plus two was four today but maybe seven tomorrow.

This feeling came into focus much later when I visited the Metropolitan Museum in New York and saw Mesopotamian tablets with cuneiform writing. They transported me back to my school years. I found them beautiful—like messages from outer space telling the story of the universe’s creation. But then I read the translation: it was something mundane like “Joe sold three kilos of tomatoes or apples.” The magic of the tablet vanished. That was the moment I understood my childhood trauma and realized what had troubled me.

When creating this series, I wanted to evoke that same sense of wonder and mystery— let people question what the images meant, even if hints of meaning were scattered throughout. For example, in Landscape with Oxygen, the numbers might suggest oxygen levels. They hint that oxygen was scarce, and this landscape is one of the few places on the planet where it still exists. These references to tragedy were deliberate. My goal was to make viewers feel the same fascination I felt as a child when I couldn’t decode the symbols before me.

CT: Your work contrasts with the current drive for immediacy and the demand for the ‘now.’ Your photos aren’t a 'neat slice of time' but rather seem to lay claim to another reality, another meaning arises from them and the passage of time, almost accidentally, becomes layered. Could we say that, in this series, you’ve given form to the passage of time?

LP: Yes, at least to a moment after some time has passed. That question intrigues me because one of my goals is to push photography beyond its usual boundaries. A key limitation of photography is that it captures a moment but immediately turns it into the past.

I think that's rooted in the old school of analog photography, which captures a moment and freezes it, turning it into the past just seconds after the photo is taken. Photography has long been described as the moment of death because it preserves the past for us to revisit. It was once believed that photography couldn't lie, but we've since learned that it often deceives more than anything else.

In my work, I aim to create images of the future, not just of the present. These pictures suggest what life could look like in the future—perhaps as a consequence of our actions today. Another aspect I find fascinating in this process is how I constantly push the boundaries of photography for myself, experimenting with scratched negatives and testing the limits of the medium.

At the same time, I've spent 30 years working with photography—exhibiting, studying, and reading extensively about it. This long engagement shapes how I approach and interpret it.

I see some of my work as crossing boundaries because I no longer limit myself to analog photography. While my practice originates from analog processes—just as we originate from our biology and are now evolving with the help of technology and artificial intelligence—I’ve expanded beyond those roots.

For years, photographers of my generation felt digital work had to mimic analog rules to maintain legitimacy. Any clear manipulation was frowned upon, as if cheating. But one day, I embraced the so-called “cheating” and found immense freedom—similar to the liberation I felt when I first scratched a negative. It was like the freedom of a painter: I could place a tree anywhere in the frame, change its color, stretch or distort it, or make it hyper-realistic.

Digital photography unlocked a new universe for me while preserving the photographic quality tied to reality. It also enhanced my ability to explore the subjective nature of memory, where perception is influenced by our chemistry. Photoshop became a powerful tool to work on this idea, giving me more ways to convey the intricate link between photography and the way we remember.

I think I’ve pushed boundaries further by incorporating digital techniques into my work while still using analog negatives. It’s like going back to the origins of photography, almost a "paleolithic" approach, and then advancing it into a new realm. In my process, it’s not just Photoshop—it’s also numbers, letters, circles, and graphic elements that I combine with photography. These elements are recognizable: numbers, dots, and even mythological references.

This merging of mediums and languages feels akin to how Latin evolved into Spanish. Photography, in this sense, evolves as it meets other languages, allowing for greater specificity and expression. For me, this blending of languages within photography enables a new kind of accuracy—a way to articulate ideas more fully.

Over generations, this layering of techniques and culture has created something undeniably photographic, even as it incorporates references beyond traditional photography. Some purists might argue, “That’s not photography anymore.” And my response is: I don’t care. Labels shouldn’t restrict us. Instead, we need to embrace the vastness of what art—and photography—can encompass.

This ties to the broader idea of discourse. Sometimes, we lack the words to describe the complexities of the world we live in—its beauty, its horrors, its enormity. Similarly, language often falls short when describing evolving concepts, like the role of women in society. Historically, women’s experiences were largely defined by men, but now, women are redefining themselves. This shift, while varied, is revolutionary. Some women feel comfortable within traditional notions of femininity, while others reject them entirely, pushing toward radical or even masculine expressions.

It’s a fascinating revolution for women, but also for men. As societal expectations shift, men too are liberated from the rigid roles assigned to them in the past. The evolving relationship between men and women creates space for new roles and perspectives. These changes impact everything, even photography.

Photography, after all, was born out of technology and science—light, time, and mathematics. But today, it’s evolving alongside advances like artificial intelligence. While painting may always rely on pigments and remain relatively static, photography is fluid. It no longer holds the same value it once did as a document of reality. There was a time when photographs were trusted as unaltered captures of truth. Now, when we see an image online or in the news, our first question is often, “Is it real?”

Photography, in this way, mirrors human evolution. Its transformation reflects our changing relationship with reality, memory, and truth. It’s no longer just about capturing the past—it’s about questioning and reimagining it in the present and for the future.

CT: In Camera Lucida,(2) which I explored as part of my research for this conversation, Roland Barthes argues that each click of the shutter is a reminder of our transient existence. The book invites us to view photography not just as a mechanical capture of light, but as a poignant exploration of humanity, memory and mortality. You have been diagnosed with leukemia at a young age, and have been battling it ever since. Do you think it has influenced your choice of medium? In what ways has it influenced your work?

LP: Photography wasn’t a rational choice for me—it was fascination from a young age. When I was eight, my father gave me a Polaroid camera. Watching the image develop before my eyes felt magical. That sense of wonder is still with me, especially in the darkroom, where the process of an image revealing itself feels almost divine. It’s an experience you miss with digital photography, where everything is immediate.

Over time, my work with photography became about exploring transformation—how I see, remember, and reinterpret experiences. Memory reshapes reality; I often think of moments with my parents that I understand differently now with the perspective life has given me.

As for leukemia, it has influenced not just my work but every aspect of my life. Facing mortality shifts your priorities. It teaches you that fame and status are fleeting. What matters is living authentically and contributing meaningfully. I see humans as scouts for the universe, each of us offering unique experiences that enrich a vast, collective intelligence.

This realization guides my art. I no longer limit myself by others’ judgments. My role is to create honestly, to discover and share, hoping my work resonates with others. Even if someone dislikes it, they’ve had an experience, and that’s what matters. The worst outcome would be indifference.

CT: Recurring themes in your work include memory, identity, colonialism, and the environment, often reconstructing realities from the fragmentation of previous ones. You describe Anthropocene Archives as 'jargons pretending to be records of posterity, fragments or archaeological findings.' Susan Sontag, in her anthology On Photography, (3) argues that it is in the nature of photography that it cannot transcend its subject. Yet, your work seems to transcend the medium, seamlessly conveying your concern with the future. Could you speak about how you blend analog and digital techniques so harmoniously, transcending the traditional boundaries of photography?

LP: Yes, exactly. The analog negative is a profoundly organic medium—made from animal gelatin derived from bone marrow, mixed with silver halides, which are sensitive to light. When light strikes the silver halides, they undergo a transformation, turning into metallic silver. That reaction is what creates the image. It’s an incredibly physical, almost magical process because it’s literally formed by light.

What I do is take this tangible object—the negative—and scan it, converting it into digital information: binary code, ones and zeros. At that moment, it transforms into something intangible, visible only on a screen. In the digital realm, it becomes fluid, almost like a new kind of magic. I can manipulate it endlessly, reshape it, and create entirely new realities from the same starting point.

This is where Susan Sontag’s argument about photography being bound to its subject starts to dissolve. Once the analog image enters the digital space, it is no longer tied to the single moment it recorded. I can revisit and reprocess it endlessly, creating infinite possibilities, each one transcending the original photograph.

This version keeps the technical explanation clear while emphasizing the poetic aspects of his process. It also ties neatly into the idea of transcending traditional photography.